Thromboembolism encompasses two interrelated conditions that are part of the same spectrum, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) (see the image below). The spectrum of disease ranges from clinically unsuspected to clinically unimportant to massive embolism causing death.

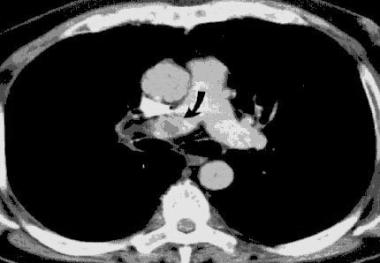

Helical CT scan of the pulmonary arteries. A filling defect in the right pulmonary artery is present, consistent with a pulmonary embolism.

Helical CT scan of the pulmonary arteries. A filling defect in the right pulmonary artery is present, consistent with a pulmonary embolism. Signs and symptoms of thromboembolism include the following:

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Workup for thromboembolism includes the following:

See Workup for more detail.

Anticoagulant medications include the following:

Thrombolytic options (for initial treatment of patients with acute, massive PE causing hemodynamic instability) include the following:

Surgical interventions include the following:

Prevention

Thromboprophylaxis reduces the incidence of DVT and fatal PE and may be achieved by pharmacologic or mechanical means. Medications used for prevention of thromboembolism include the following:

Mechanical approaches to thromboprophylaxis include the following:

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

NextThromboembolism encompasses two interrelated conditions that are part of the same spectrum, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). PE is the obstruction of blood flow to one or more arteries of the lung by a thrombus lodged in a pulmonary vessel, as shown in the image below. (See Pathophysiology and Etiology.)

Pulmonary embolism within the pulmonary artery.

Pulmonary embolism within the pulmonary artery. PE and DVT can occur in the setting of disease processes, following hospitalization for serious illness, or following major surgery. In 1856, Virchow demonstrated that 90% of all clinically important PEs result from DVT occurring in the deep veins of the lower extremities, proximal to and including the popliteal veins. However, emboli also can originate from the pelvic veins, the inferior vena cava, and the upper extremities. (See Pathophysiology, Etiology, Presentation, and Workup)[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Thromboembolic disease is the third most common acute cardiovascular disease, after cardiac ischemic syndromes and stroke. The spectrum of disease ranges from clinically unsuspected to clinically unimportant to massive embolism causing death, and indeed DVT and PE frequently remain undiagnosed because they may not be suspected clinically. Untreated acute proximal DVT causes clinical PE in 33-50% of patients. Untreated PE often is recurrent over days to weeks and can either improve spontaneously or cause death. (See Epidemiology, Presentation, and Workup.)

The clinical practice guidelines published in 2009 by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) regarding the prevention of PE in patients undergoing total hip replacement (THR) or total knee replacement (TKR) included the recommendation of mechanical prophylaxis and early mobilization for all patients. (See Treatment and Medication.)[6, 7, 8]

The following statements summarize the recommendations for chemoprophylaxis:

AAOS 2011 guidelines, addressing the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) disease in the patient undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty, recommend patient assessment for a history of previous VTE, bleeding disorders, and other conditions that place the patient at higher risk for bleeding (eg, active liver disease).[9]

Other guidelines

A study by Khokhar et al indicated that there is a lack of uniformity among venous thromboprophylactic guidelines for elective knee arthroplasty. Reviewing 12 guidelines, the investigators found that although almost all of them advocated the use of LMWH and fondaparinux (a synthetic, pentasaccharide anticoagulant), recommendations for other drugs varied, as did drug dosages, duration, and recommendation grades.[10]

In an article addressing the differences between the antithrombotic guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and AAOS, the authors noted that recommendation variations were based on methodology and evidence differences.[6]

A thrombus is a solid mass composed of platelets and fibrin with a few trapped red and white blood cells that forms within a blood vessel. Hypercoagulability or obstruction leads to the formation of a thrombus in the deep veins of the legs, pelvis, or arms.

As the clot propagates, proximal extension occurs, which may dislodge or fragment and embolize to the pulmonary arteries. This causes pulmonary artery obstruction, and the release of vasoactive agents (ie, serotonin) by platelets increases pulmonary vascular resistance. The arterial obstruction increases alveolar dead space and leads to redistribution of blood flow, thus impairing gas exchange due to the creation of low ventilation-perfusion areas within the lung.

Stimulation of irritant receptors causes alveolar hyperventilation. Reflex bronchoconstriction occurs and augments airway resistance. Lung edema decreases pulmonary compliance. The increased pulmonary vascular resistance causes an increase in right ventricular afterload, and tension rises in the right ventricular wall, which may lead to dilatation, dysfunction, and ischemia of the right ventricle. Right heart failure can occur and lead to cardiogenic shock and even death. In the presence of a patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect, paradoxical embolism may occur, as well as right-to-left shunting of blood with severe hypoxemia.

Risk factors for thromboembolic disease can be divided into a number of categories, including patient-related factors, disease states, surgical factors, and hematologic disorders. Risk is additive.

Patient-related factors include age older than 40 years, obesity, varicose veins, the use of estrogen in pharmacologic doses (ie, oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy), and immobility.

Disease states such as malignancy, congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, recent myocardial infarction, inflammatory bowel disease, spinal cord injury with paralysis, and pelvic, hip, or long-bone fracture confer increased risk of thromboembolic disease.

Surgical factors are related to procedure type and procedure duration. Fifty percent of patients who have undergone hip surgery have a proximal DVT on the same side as the hip surgery. This is thought to be due to a twisting of the femoral vein during total hip replacement. The incidence of DVT is higher in patients who have undergone knee surgery.[10]

In a study of patients following pelvic surgery, 40-80% had calf DVT, and 10-20% had thigh vein thromboses. Fatal PE developed in 1-5% of patients. The risk for thromboembolic disease has been shown to be increased with coronary artery bypass grafting, urologic surgery, and neurosurgery.[11]

One study identified the following four risk factors as being highly predictive of venous thromboembolism among hospitalized medical patients[12] :

This four-element risk assessment model was accurate at identifying patients at risk of developing venous thromboembolism within 90 days and was more effective than the Kucher Score, a risk assessment score.[12]

Hematologic disorders that increase thromboembolic risk include the following:

Activated protein C resistance (factor V Leiden)

Risk prediction algorithm

A prospective, open cohort study developed a new clinical risk prediction algorithm (QThrombosis) to assess the risk of venous thromboembolism development. Using routinely collected data from 564 general practices in England and Wales, this study found that independent predictors at 1 and 5 years included the following[14] :

Oral contraceptive use, tamoxifen use, and hormone replacement therapy were noted in the study as independent predictors in women. This risk assessment can help to identify patients at high risk of venous thromboembolism and may help determine a course of treatment.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that over a 3-year period (2007-2009), there was an estimated annual average of 547,596 hospitalizations in which venous thromboembolism was diagnosed, for patients aged 18 years or older.[15, 16]

Over the same period, for the same age group, an estimated average of 348,558 hospitalizations in which DVT was diagnosed occurred annually, and an estimated average of 277,549 hospitalizations in which PE was diagnosed occurred annually. Among these patients, an estimated average of 78,511 hospitalizations in which both DVT and PE were diagnosed occurred annually.

Thromboembolism has a significant impact on morbidity and mortality internationally. A multinational report of European Union countries estimated that the total number of symptomatic, nonfatal VTE events per annum was more than 465,000 cases of DVT and more than 295,000 cases of PE. The authors estimated more than 370,000 VTE-related deaths, and 7% were diagnosed premortem and 34% were sudden fatal PE.[17]

The incidence of thromboembolism is higher in African Americans than it is in whites, whereas Asians have a lower incidence than do African Americans and whites. PE occurs more frequently in males than in females.

According to the CDC, the estimated average annual number (for years 2007-2009) of hospitalizations in which venous thromboembolism was diagnosed was as follows for adult males and females[16] :

Age is a risk factor for thromboembolic disease, being greater in older patients than in younger ones. The risk doubles with each decade in persons older than 40 years.

According to the CDC, the estimated annual average number (for years 2007-2009) of hospitalizations in which venous thromboembolism was diagnosed was as follows for specific adult age groups[16] :

The estimated annual average rate (for years 2007-2009) of hospitalizations in which venous thromboembolism was diagnosed was as follows for specific adult age groups:

Thromboembolic disease accounts for approximately a quarter of a million hospitalizations in the United States annually and for about 5-10% of all deaths.

About one third of PE cases are fatal. Of these, 67% are not diagnosed ante mortem, and 34% occur rapidly. A high rate of clinically unsuspected DVT and PE leads to significant diagnostic and therapeutic delays, and this accounts for substantial morbidity and mortality.

Studies demonstrate a 95% risk reduction with treatment of thromboembolic disease. There is, however, a risk of recurrence following the discontinuance of treatment that is related to the type and number of risk factors the patient has and whether they persist following completion of treatment. Five to seven percent of all recurrences are fatal.

For the success and ease of outpatient treatment, patients on oral warfarin anticoagulation should be instructed on the impact of dietary choices on treatment goals and the need for frequent monitoring. Instruction on the avoidance of reversible risk factors would be helpful in preventing disease recurrence.

The best approach to patient education is one that starts with open communication with the patient and family, reviewing not only the procedure or planned surgical intervention, but also potential complications.

For patient education information, see the Lung Disease and Respiratory Health Center, as well as Pulmonary Embolism and Deep Vein Thrombosis (Blood Clot in the Leg, DVT).

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved