Sjögren syndrome is a systemic chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltrates in exocrine organs. Most individuals with Sjögren syndrome present with sicca symptoms, such as xerophthalmia (dry eyes), xerostomia (dry mouth), and parotid gland enlargement, which is seen in the image below.[1] (See Presentation.)

Marked bilateral parotid gland enlargement in a patient with primary Sjögren syndrome. Sicca syndrome is a common clinical finding.

Marked bilateral parotid gland enlargement in a patient with primary Sjögren syndrome. Sicca syndrome is a common clinical finding.

In addition, numerous extraglandular features may develop, such as the following:

About 50% of patients with Sjögren syndrome have cutaneous findings, such as dry skin (xeroderma), palpable and nonpalpable purpura, and/or urticaria.[2] (See Etiology, Presentation, and Workup.)

Primary Sjögren syndrome occurs in the absence of another underlying rheumatic disorder, whereas secondary Sjögren syndrome is associated with another underlying rheumatic disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or scleroderma. Given the overlap of Sjögren syndrome with many other rheumatic disorders, it is sometimes difficult to determine whether a clinical manifestation is solely a consequence of Sjögren syndrome or is due to one of its overlapping disorders.

Importantly, classic clinical features of Sjögren syndrome may also be seen in infections with certain viruses. These include hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and human T-cell lymphotrophic virus (HTLV). (See DDx.)

Treatment for Sjögren syndrome is largely based on symptoms (eg, lotion for dry skin, artificial tears for dry eyes). Rituximab has shown promise in the treatment of severe extraglandular manifestations (eg, vasculitis, cryoglobulinemia, peripheral neuropathy). Patients must be monitored carefully for the potential development of lymphoma, as the risk for this disease is significantly higher than in the general population. (See Treatment and Medication.)

For more information on other aspects of Sjögren syndrome, see Pediatric Sjögren Syndrome and Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Sjögren Syndrome.

A number of classification criteria for Sjögren syndrome were designed primarily for clinical research studies but are also often used to help guide clinical diagnoses. The American-European Consensus Group’s criteria for the classification of Sjögren syndrome were proposed in 2002 and are the most commonly used criteria for the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. A new set of classification criteria has been developed by the Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance (SICCA) investigators and accepted as a provisional criteria set by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 2012.

The American-European Consensus Group (AECG) criteria for the classification of Sjögren syndrome are outlined below.[3, 4] These criteria allow a diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome in patients without sicca symptoms or who have not undergone a biopsy.

According to the American-European classification system (as modified by Tzioufas and Voulgarelis[5] ), diagnosis of primary Sjögren syndrome requires at least four of the criteria listed below; in addition, either criterion number 5 or criterion number 6 must be included. Sjögren syndrome can be diagnosed in patients who have no sicca symptoms if three of the four objective criteria are fulfilled. The criteria are as follows:

Secondary Sjögren syndrome is diagnosed when, in the presence of a connective-tissue disease, symptoms of oral or ocular dryness exist in addition to criterion 3, 4, or 5, above.

Application of these criteria has yielded a sensitivity of 97.2% and a specificity of 48.6% for the diagnosis of primary Sjögren syndrome. For secondary Sjögren syndrome, the specificity is 97.2% and the sensitivity, 64.7%.[6]

Exclusion criteria include any of the following:

These classification criteria were developed by SICCA investigators in an effort to improve specificity of criteria used for entry into clinical trials, especially in light of the emergence of biologic agents as potential treatments for Sjögren syndrome and their associated comorbidities. This high specificity makes the ACR criteria more suitable for application in situations in which misclassification may present a health risk. They were accepted by the ACR as a provisional criteria set in 2012.[7]

According to the ACR criteria, the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome requires at least two of the following three findings:

In comparison with commonly used AECG criteria, the ACR criteria are based entirely on a combination of objective tests that assess the three main components of Sjögren syndrome (serologic, ocular, and salivary) and do not include criteria based on subjective symptoms of ocular and oral dryness.

Application of these criteria has yielded a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 95% for the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. These criteria do not distinguish between primary and secondary forms of Sjögren syndrome.

Complications related to Sjögren syndrome include the following (see Prognosis, Treatment, and Medication):

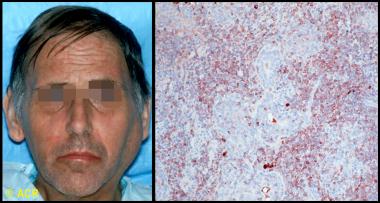

Clinical photograph and photomicrograph of a 48-year-old man with Sjögren syndrome with a large left parotid mass. On biopsy, B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type was identified. Microscopic section of parotid biopsy, stained with immunoperoxidase for kappa light chains (brown-stained cells), showed monoclonal population of B cells, confirming the diagnosis.

Clinical photograph and photomicrograph of a 48-year-old man with Sjögren syndrome with a large left parotid mass. On biopsy, B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type was identified. Microscopic section of parotid biopsy, stained with immunoperoxidase for kappa light chains (brown-stained cells), showed monoclonal population of B cells, confirming the diagnosis.

Educate patients with Sjögren syndrome on avoidance strategies and self-care issues for the treatment of dry mouth, eyes, skin, and vagina. Patient education pamphlets regarding the disease are available through the Arthritis Foundation. The Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation, founded in 1983, is a good resource for patients. The foundation can be contacted at 6707 Democracy Blvd, Ste 325, Bethesda, MD, 20817; (800) 475-6473, (301) 530-4415 (fax).

For patient education information, see the Arthritis Center, as well as Sjögren’s Syndrome.

NextSjögren syndrome can occur as a primary disease of exocrine gland dysfunction or in association with several other autoimmune diseases (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, systemic sclerosis, cryoglobulinemia, polyarteritis nodosa). These primary and secondary types occur with similar frequency, but the sicca complex seems to cause more severe symptoms in the primary form.

Virtually all organs may be involved. The disease commonly affects the eyes, mouth, parotid gland, lungs, kidneys, skin, and nervous system.

The etiology of Sjögren syndrome is not well understood. The presence of activated salivary gland epithelial cells expressing major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules and the identification of inherited susceptibility markers suggest that environmental or endogenous antigens trigger a self-perpetuating inflammatory response in susceptible individuals. In addition, the continuing presence of active interferon pathways in Sjögren syndrome suggests ongoing activation of the innate immune system.[8, 9] Together, these findings suggest an ongoing interaction between the innate and acquired immune systems in Sjögren syndrome.

The frequency of HLA-DR52 in patients with primary Sjögren syndrome is estimated to be 87%, but it is also significantly increased in secondary Sjögren syndrome that occurs with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus.

The genetic associations in Sjögren syndrome vary among ethnic groups. In white persons, for instance, the condition is linked to human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR3, HLA-DQ2, and HLA-B8,[10] whereas the linkage is to HLA-DRB1*15 in Spanish persons[11] and to HLA-DR5 in Greek and Israeli persons.[12]

Some evidence indicates that the true association of Sjögren syndrome may be with HLA-DQA1, which is in linkage disequilibrium with HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR5.[13] These HLA associations appear restricted to individuals with Sjögren syndrome who have antibodies to the antigens SSA and SSB rather than to the disease manifestations themselves.[14]

Viruses are viable candidates as environmental triggers, although proof of causation has remained elusive, and certainly no single virus has been implicated. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), HTLV-1, human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) may have a role. Sjögrenlike syndromes are seen in patients infected with HIV, HTLV-1, and hepatitis C.[15, 16, 17]

Damage and/or cell death due to viral infection or other causes may provide triggering antigens to Toll-like receptors in or on dendritic or epithelial cells, which, by recognizing pathogen-associated patterns, are activated and begin producing cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules. As T and B lymphocytes migrate into the gland, they themselves become activated by dendritic and epithelial cells, thereafter acting as antigen-presenting cells.[18]

Expressed antigens include SSA/Ro, SSB/La, alpha-fodrin and beta-fodrin, and cholinergic muscarinic receptors.[14] Dendritic cell triggering by immune complexes formed from SSA ̶ anti-SSA (or other immune complexes) may propagate the ongoing innate and acquired immune activation.

The pathology of a typical involved salivary or lacrimal gland in Sjögren syndrome reveals aggregations of lymphocytes—periductal at first, then panlobular. These cells are primarily CD4 T cells (75%) and memory cells, with 10% B cells and immunoglobulin-secreting plasma cells. Although individual lobules can be destroyed, salivary gland biopsy samples from patients with Sjögren syndrome typically retain 40%-50% of their viable glandular structure. Therefore, inflammatory destruction of salivary and lacrimal glands may not fully account for the symptoms of Sjögren syndrome.[19]

Studies suggest that the disease process of Sjögren syndrome has a neuroendocrine component. Proinflammatory cytokines released by epithelial cells and lymphocytes may impair neural release of acetylcholine. In addition, antibodies to acetylcholine (muscarinic) receptors may interfere with the neural stimulation of local glandular secretion,[20] perhaps by interfering with aquaporin.[21] Moreover, a study reports that M3 muscarinic receptor antibodies may cause autonomic dysfunction in patients with Sjögren syndrome.[22, 23]

Current studies have also focused on the role of apoptotic mechanisms in the pathogenesis of primary Sjögren syndrome. A defect in Fas-mediated apoptosis, which is necessary for down-regulation of the immune response, can result in a chronic inflammatory destruction of the salivary gland, resembling Sjögren syndrome.[24]

Owing to these structural and functional changes in the lacrimal and salivary glands, their aqueous output is diminished. In the eye, tear hyperosmolarity results and is itself a proinflammatory stimulus, resulting in an inflammatory cascade on the ocular surface,[25] with evidence of immune activation of the conjunctival epithelium and local cytokine and metalloproteinase production. Damage to the corneal epithelium, already vulnerable due to inadequate tear film protection, ensues, with resultant epithelial erosions and surface irregularity.

Extraglandular involvement in Sjögren syndrome manifests in part as hypergammaglobulinemia and the production of multiple autoantibodies, especially ANA and RF. This may be due to polyclonal B-cell activation, but the cause of this expanded activation is not known.

Involvement of other organs and tissues may result from effects of these antibodies, immune complexes, or lymphocytic infiltration and occurs in one third of patients with Sjögren syndrome. Prolonged hyperstimulation of B cells may lead to disturbances in their differentiation and maturation and may account for the greatly increased incidence of lymphoma in these patients.[26]

Sex hormones may influence the immunologic manifestations of primary Sjögren syndrome, because the disease is much more common in women than in men. The prevalence of serologic markers tends to be lower in male patients than in female patients. Although the role of sex hormones (eg, estrogens, androgens) in the pathogenesis of primary Sjögren syndrome remains unknown, adrenal and gonadal steroid hormone deficiency probably affects immune function.

In the United States, Sjögren syndrome is estimated to be the second most common rheumatologic disorder, behind SLE. Sjögren syndrome affects 0.1-4% of the population. This wide range, in part, reflects the lack of uniform diagnostic criteria.[27] Internationally, comparative studies between different ethnic groups have suggested that Sjögren syndrome is a homogeneous disease that occurs worldwide with similar prevalence and affects 1-2 million people.

The female-to-male ratio of Sjögren syndrome is 9:1. Sjögren syndrome can affect individuals of any age but is most common in elderly people. Onset typically occurs in the fourth to fifth decade of life.

Sjögren syndrome carries a generally good prognosis. In patients who develop a disorder associated with Sjögren syndrome, the prognosis is more closely related to the associated disorder (eg, SLE, lymphoma).

Although salivary and lacrimal function generally stabilize, the presence of SSA and/or hypocomplementemia may predict a decline in function.[28]

Morbidity associated with Sjögren syndrome is mainly associated with the gradually decreased function of exocrine organs, which become infiltrated with lymphocytes. The increased mortality rate associated with the condition is primarily related to disorders commonly associated with Sjögren syndrome, such as SLE, RA, and primary biliary cirrhosis. Patients with primary Sjögren syndrome who do not develop a lymphoproliferative disorder have a normal life expectancy.[29]

Among patients with Sjögren syndrome, the incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is 4.3% (18.9 times higher than in the general population), with a median age at diagnosis of 58 years. The mean time to the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma after the onset of Sjögren syndrome is 7.5 years.

The most common histologic subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Sjögren syndrome is mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, which can develop in any nonlymphoid tissue infiltrated by periepithelial lymphoid tissue—most commonly the salivary glands, but also the stomach, nasopharynx, skin, liver, kidneys, and lungs. The progression of these infiltrates to lymphoma occurs slowly and in a stepwise fashion. Lymphoma is present at more than 1 site in 20% of patients at initial diagnosis.

The results of one study suggest that diagnostic labial salivary gland tissue biopsy can be used to detect germinal center ̶ like lesions, which can be a highly predictive and easily obtained marker for non-Hodgkin lymphoma in primary Sjögren syndrome patients.[30]

Patients at an increased risk of lymphoma include those with regional or generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, palpable purpura, leukopenia, renal insufficiency, loss of a previously positive polyclonal gammopathy or RF, development of a monoclonal gammopathy, or the development of a monoclonal cryoglobulinemia.

Children born to mothers with antibodies against SSA/Ro are at an increased risk of neonatal lupus and congenital heart block. If one such child develops congenital heart block, the risk for congenital heart block during a subsequent pregnancy is 15%.

Patients with Sjögren syndrome who have antiphospholipid antibodies can develop the clinical features of antiphospholipid syndrome, which include increased fetal wastage and vascular thromboses.

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved