Lupus nephritis is histologically evident in most patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), even those without clinical manifestations of renal disease. Evaluating renal function in SLE patients is important because early detection and treatment of renal involvement can significantly improve renal outcome. See the image below.

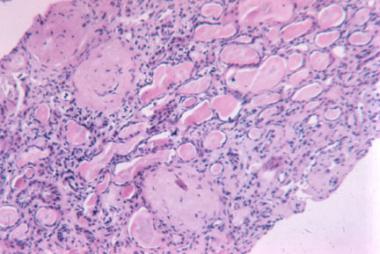

Advanced sclerosis lupus nephritis. International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society 2003 class VI (×100, hematoxylin-eosin).

Advanced sclerosis lupus nephritis. International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society 2003 class VI (×100, hematoxylin-eosin).

Patients with lupus nephritis may report the following:

Physical findings may include the following:

See Presentation for more detail.

Laboratory tests to evaluate renal function in SLE patients include the following:

Laboratory tests for SLE disease activity include the following:

Renal biopsy should be considered in any patient with SLE who has clinical or laboratory evidence of active nephritis, especially upon the first episode of nephritis.

Lupus nephritis is staged according to the classification revised by the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) and the Renal Pathology Society (RPS) in 2003, as follows:

See Workup for more detail.

The principal goal of therapy in lupus nephritis is to normalize renal function or, at least, to prevent the progressive loss of renal function. Therapy differs, depending on the pathologic lesion.

Key points of American College of Rheumatology guidelines for managing lupus nephritis are as follows:

Patients with class V lupus nephritis are generally treated with prednisone for 1-3 months, followed by tapering for 1-2 years if a response occurs. If no response occurs, the drug is discontinued. Immunosuppressive drugs are generally not used unless renal function worsens or a proliferative component is present on renal biopsy samples.

Investigational therapies for lupus nephritis and SLE include the following:

Patients with end-stage renal disease require dialysis and are good candidates for kidney transplantation. Hemodialysis is preferred to peritoneal dialysis.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

NextLupus nephritis, one of the most serious manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), usually arises within 5 years of diagnosis; however, renal failure rarely occurs before American College of Rheumatology criteria for classification are met.

Lupus nephritis is histologically evident in most patients with SLE, even those without clinical manifestations of renal disease. The symptoms of lupus nephritis are generally related to hypertension, proteinuria, and renal failure. (See Presentation.)

Evaluating renal function in patients with SLE to detect any renal involvement early is important because early detection and treatment can significantly improve renal outcome. Renal biopsy should be considered in any patient with SLE who has clinical or laboratory evidence of active nephritis, especially upon the first episode of nephritis. (See Workup.)

The principal goal of therapy in lupus nephritis is to normalize renal function or, at least, to prevent the progressive loss of renal function. Therapy differs depending on the pathologic lesion. With the advent of more aggressive immunosuppressive and supportive therapy, rates of renal involvement and patient survival are improving. (See Treatment.)

Autoimmunity plays a major role in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. The immunologic mechanisms include production of autoantibodies directed against nuclear elements. The characteristics of the nephritogenic autoantibodies associated with lupus nephritis are as follows[1] :

These autoantibodies form pathogenic immune complexes intravascularly, which are deposited in glomeruli. Alternatively, autoantibodies may bind to antigens already located in the glomerular basement membrane, forming immune complexes in situ. Immune complexes promote an inflammatory response by activating complement and attracting inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.[2, 3]

The histologic type of lupus nephritis that develops depends on numerous factors, including the antigen specificity and other properties of the autoantibodies and the type of inflammatory response that is determined by other host factors. In more severe forms of lupus nephritis, proliferation of endothelial, mesangial, and epithelial cells and the production of matrix proteins lead to fibrosis.[4]

Glomerular thrombosis is another mechanism that may play a role in pathogenesis of lupus nephritis, mainly in patients with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, and is believed to be the result of antibodies directed against negatively charged phospholipid-protein complexes.[2]

As with many autoimmune disorders, evidence suggests that genetic predisposition plays an important role in the development of both SLE and lupus nephritis. Multiple genes, many of which are not yet identified, mediate this genetic predisposition (see Table 1 below).[5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 4, 11]

Table 1. Genes Associated With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (Open Table in a new window)

Gene Locus Gene Name Gene Product 1p13.2 PTPN22 Lymphoid-specific protein tyrosine phosphatase 1q21-q23 CRP CRP 1q23 FCGR2A, FCGR2B FcγRIIA (R131), FcγRIIB 1q23 FCGR3A, FCGR3B FcγRIIIA (V176), FcγRIIIB 1q31-q32 IL10 IL-10 1q36.12 C1QB C1q deficiency 2q32.2-q32.3 STAT4 Signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 2q33 CTLA4 Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) 6p21.3 HLA-DRB1 HLA-DRB1: DR2/*1501, DR3/*0301C1q deficiency 6p21.3 C2, C4A, C4B C2, C4 deficiencies 6p21.3 TNF TNF-a (promoter, -308) 10q11.2-q21 MBL2 Mannose-binding lectin CRP = C-reactive protein; HLA = human leukocyte antigen; IL = interleukin; TNF = tumor necrosis factor.SLE is more common in first-degree relatives of patients with SLE (familial prevalence, 10-12%). Concordance rates are higher in monozygotic twins (24-58%) than in dizygotic twins (2-5%), supporting an important role for genetics in the development of SLE. However, the concordance rate in monozygotic twins is not 100%, suggesting that environmental factors trigger development of clinical disease.

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II genes include the following:

Complement genes include the following:

FcγR genes include the following:

Other relevant genes include the following:

The initial autoantibody response appears to be directed against the nucleosome, which arises from apoptotic cells.[4, 12, 13]

Patients with SLE have poor clearance mechanisms for cellular debris. Nuclear debris from apoptotic cells induces plasmacytoid dendritic cells to produce interferon-α, which is a potent inducer of the immune system and autoimmunity.[14, 15, 16]

Autoreactive B lymphocytes, which are normally inactive, become active in SLE because of a malfunction of normal homeostatic mechanisms, resulting in escape from tolerance. This leads to the production of autoantibodies. Other autoantibodies, including anti-dsDNA antibodies, develop through a process of epitope spreading. These autoantibodies develop over time, in an orderly fashion, months to years before the onset of clinical SLE.[17]

In a multi-ethnic international cohort of patients enrolled within 15 months (mean, 6 months) after SLE diagnosis and assessed annually, lupus nephritis occurred in 700 of 1827 patients (38.3%). Lupus nephritis was frequently the initial presentation of SLE; it was identified at enrollment in 80.9% of cases. Patients with nephritis were younger, more frequently men and of African, Asian, and Hispanic race/ethnicity.[18]

In a study of a large Spanish registry, lupus nephritis was histologically confirmed in 1092 of 3575 patients with SLE (30.5%). The mean age at lupus nephritis diagnosis was 28.4 years. The risk for lupus nephritis development was significantly higher in men, in younger individuals, and in Hispanics. Patients receiving antimalarials had a significantly lower risk of developing lupus nephritis.[19]

Most patients with SLE develop lupus nephritis early in their disease course. SLE is more common among women in the third decade of life, and lupus nephritis typically occurs in patients aged 20-40 years.[20] Children with SLE are at a higher risk of renal disease than adults and tend to sustain more disease damage secondary to more aggressive disease and treatment-associated toxicity.[21, 22, 23]

Because the overall prevalence of SLE is higher in females (ie, female-to-male ratio of 9:1), lupus nephritis is also more common in females; however, clinical renal disease has a worse prognosis and is more common in males with SLE.[20]

SLE is more common in African Americans and Hispanics than in white people. Particularly severe lupus nephritis may be more common in African Americans and Asians than in other ethnic groups.[20]

Over the past 4 decades, changes in the treatment of lupus nephritis and general medical care have greatly improved both renal involvement and overall survival. During the 1950s, the 5-year survival rate among patients with lupus nephritis was close to 0%. The subsequent addition of immunosuppressive agents such as intravenous (IV) pulse cyclophosphamide has led to documented 5- and 10-year survival rates as high as 85% and 73%, respectively.[24]

Morbidity associated with lupus nephritis is related to the renal disease itself, as well as to treatment-related complications and comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease and thrombotic events. Progressive renal failure leads to anemia, uremia, and electrolyte and acid-based abnormalities. Hypertension may lead to an increased risk of coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular accident.

Nephrotic syndrome may lead to edema, ascites, and hyperlipidemia, adding to the risk of coronary artery disease and the potential for thrombosis. The findings from one study indicate that patients with lupus nephritis, particularly early-onset lupus nephritis, are at increased risk for morbidity from ischemic heart disease.[25]

In a study of 56 children (<18 years) with either global or segmental diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis, long-term renal outcomes were similar. Most patients reached adulthood but sustained significant renal damage. Complete remission rates were 50% and 60% in the global and segmental groups, respectively. Renal survival rates, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate of ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, were 93%, 78%, and 64 % at 1, 5, and 10 years, respectively, and corresponding patient survival rates were 98%, 96%, and 91%, respectively, with similar rates in the global and segmental groups.[26]

Therapy with corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and other immunosuppressive agents increases the risk of infection. Long-term corticosteroid therapy may lead to osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension, among other complications. Cyclophosphamide therapy may cause cytopenias, hemorrhagic cystitis, infertility, and an increased risk of malignancy.

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved