Traumatic injuries of the scapula have received little attention in the literature because they are uncommon. Scapula fractures account for approximately 1% of all fractures. Historically, scapula fractures have been treated by closed means. One of the earliest descriptions of treating scapula fractures was published in 1805 in Desault's treatise on fractures. Hardegger et al reported that if significant displacement occurs, conservative treatment alone cannot restore congruence, and stiffness and pain may result, thereby indicating open reduction and stabilization.[1]

Their relative infrequency notwithstanding, scapula fractures have a high association with other injuries.[2, 3] Research shows that 80-95% of scapula fractures have associated injuries, which may be multiple and/or life-threatening. As a result, diagnosis and treatment of scapular injuries may be delayed or suboptimal. Long-term functional impairment may occur. As more focus is placed on the proper management of scapular injuries, functional outcomes should improve.[4]

Most scapula fractures can be managed effectively with closed treatment. Some injuries with significant displacement have poor long-term outcomes for the shoulder and the upper extremity as a whole if treated with closed techniques. This article reviews closed management of scapula fractures, discusses open treatment, and provides guidelines for injuries that require operative intervention.

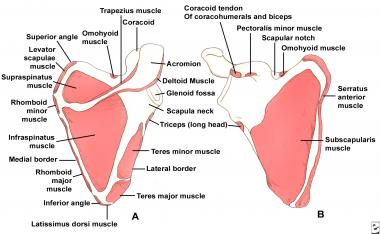

NextThe scapula serves as the attachment site for 18 muscles, which link it to the thorax, spine, and upper extremity. (See the image below.) The subscapularis covers the anterior surface, and the serratus anterior attaches to the inferior angle along the anterior medial border. The supraspinatus and the infraspinatus lie on the posterior border of the scapula. Overlying them is the trapezius, which inserts on the spine and the clavicle. The deltoid originates from the scapular spine, acromion, and anterior clavicle. Many other muscles attach to the scapular margins.

(Click Image to enlarge.) Scapular anatomy. Muscle origin and insertion.

(Click Image to enlarge.) Scapular anatomy. Muscle origin and insertion.

The coracoid process projects from the superior border of the scapula. The coracobrachialis and the short head of the biceps originate from the coracoid, and the pectoralis minor inserts on the coracoid. The brachial plexus and the axillary artery run posterior to the pectoralis minor tendon. The scapular notch lies just medial to the coracoid base and is covered by the transverse scapular ligament. The suprascapular nerve runs under the ligament, and the suprascapular artery passes over it.

The acromion is the lateral projection from the spine of the scapula. The spinoglenoid notch is the gap between the acromion and the glenoid neck of the scapula. The suprascapular nerve and vessels pass through the notch en route to the infraspinatus.

Typically, scapula fractures result from high-energy trauma.[5] Direct forces are most common, but indirect mechanisms can also be responsible. An example of an indirect force is a fall on an outstretched arm that causes the humeral head to impact on the glenoid cavity.

Scapula fractures account for 1% of all fractures, 3% of shoulder girdle injuries, and 5% of all shoulder fractures. Approximately 50% of scapula fractures involve the body and spine. Fractures of the glenoid neck constitute about 25% of all scapula fractures, whereas fractures of the glenoid cavity (glenoid rim and fossa) make up approximately 10% of scapula fractures. The acromial and coracoid processes account for 8% and 7%, respectively.

Because of the low incidence of scapula fractures, little in the way of outcome data exists. Hardegger et al reported 79% good-to-excellent results associated with five displaced glenoid neck fractures treated surgically (6.5-year follow-up).[1] Kavanaugh et al at the Mayo Clinic reviewed 10 displaced glenoid cavity fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) and found this to be a useful and safe technique that can restore excellent function of the shoulder.[6]

Nonoperative treatment can sometimes result in malunion, leading to poor range of motion, chronic pain, and poor cosmesis. Cole et al report that surgical reconstruction of malunited scapula neck or body fractures can yield good functional and cosmetic outcomes.[7]

Until more data are available, it is reasonable to predict a good-to-excellent functional result if surgical management restores normal or near-normal anatomy, articular congruity, and glenohumeral stability; if surgery provides secure fixation; and if a well-structured and intensive rehabilitation program is implemented.[8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved