Genu valgum is the Latin-derived term used to describe knock-knee deformity. Whereas many otherwise healthy children have knock-knee deformity as a passing trait, some individuals retain or develop this deformity as a result of hereditary (see the image below) or genetic disorders or metabolic bone disease.

This 9-year-old patient has symmetrical and progressive genu valgum caused by a hereditary form of metaphyseal dysplasia. One method of treatment is to undertake bilateral femoral and tibial/fibular osteotomies, securing these with internal plates or external frames. However, the hospitalization and the attendant cost and risks, including peroneal nerve palsy and compartment syndrome, make this a daunting task for the surgeon and family alike. Furthermore, mobilization and weightbearing may require physical therapy but must be delayed pending initial healing of the bones.

This 9-year-old patient has symmetrical and progressive genu valgum caused by a hereditary form of metaphyseal dysplasia. One method of treatment is to undertake bilateral femoral and tibial/fibular osteotomies, securing these with internal plates or external frames. However, the hospitalization and the attendant cost and risks, including peroneal nerve palsy and compartment syndrome, make this a daunting task for the surgeon and family alike. Furthermore, mobilization and weightbearing may require physical therapy but must be delayed pending initial healing of the bones.

The typical gait pattern is circumduction, requiring that the individual swing each leg outward while walking in order to take a step without striking the planted limb with the moving limb. Not only are the mechanics of gait compromised but also, with significant angular deformity, anterior and medial knee pain are common. These symptoms reflect the pathologic strain on the knee and its patellofemoral extensor mechanism.

For persistent genu valgum, treatment recommendations have included a wide array of options, ranging from lifestyle restriction and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to bracing, exercise programs, and physical therapy. In recalcitrant cases, surgery may be advised. No consensus exists regarding the optimal treatment. Some surgeons focus (perhaps inappropriately) on the patella itself, favoring arthroscopic or open realignment techniques. However, if valgus malalignment of the extremity is significant, corrective osteotomy or, in the skeletally immature patient, hemiepiphysiodesis may be indicated.

Osteotomy indications and techniques have been well described in standard textbooks and orthopedic journals and are not the focus of this article. Hemiepiphysiodesis can be accomplished by using the classic Phemister bone block technique, the percutaneous method, hemiphyseal stapling, or the application of a single two-hole plate and screws around the physis. The senior author, having experience in each of these techniques, developed the last of these techniques in order to solve two of the problems sometimes encountered with staples—namely, hardware fatigue and migration.

The focus of this article is on the indications, techniques, complications, and outcome of guided growth using the reversible plate technique for the correction of pathologic genu valgum.

NextThe radiographic parameters relevant to defining genu valgum are best measured on a full-length standing anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the legs. The angle is measured between the femoral shaft and its condyles (the normal angle is 84°); this is referred to as the lateral distal femoral angle. The other relevant angle is the proximal medial tibial angle; this is the angle between the tibial shaft and its plateaus (the normal angle is 87°).

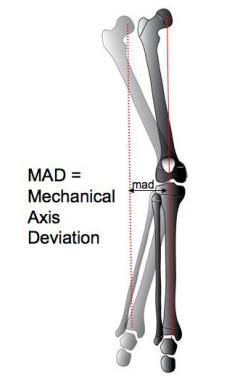

The mechanical axis (center of gravity) is a straight line drawn from the center of the femoral head to the center of the ankle; this should bisect the knee. Allowing for variations of normal, an axis within the two central quadrants (zones +1 or -1) of the knee is deemed acceptable.

With normal alignment, the lower-extremity lengths are equal, and the mechanical axis bisects the knee when the patient is standing erect with the patellae facing forward. This position places relatively balanced forces on the medial and lateral compartments of the knee and on the collateral ligaments, while the patella remains stable and centered in the femoral sulcus.

With normal alignment, the physes and epiphyses are subjected to physiologic and intermittent compression and tension and, thus, are shielded from pathologic stress. Balanced growth preserves straight legs, symmetrical limb lengths, and normal function. In genu valgum, as the mechanical axis shifts laterally (see the image below), pathologic stress is placed on the lateral femur and tibia, inhibiting growth and possibly leading to a vicious cycle.

This diagram depicts genu valgum involving the right leg (lighter shade), where the mechanical axis falls outside the knee. The goal of treatment is to realign the limb and neutralize the mechanical axis (dotted red line), thereby mitigating the effects of gravity through guided growth of the femur and/or tibia (whatever is required to maintain a horizontal knee joint axis). The darker shade depicts normal alignment with the mechanical axis now bisecting the knee.

This diagram depicts genu valgum involving the right leg (lighter shade), where the mechanical axis falls outside the knee. The goal of treatment is to realign the limb and neutralize the mechanical axis (dotted red line), thereby mitigating the effects of gravity through guided growth of the femur and/or tibia (whatever is required to maintain a horizontal knee joint axis). The darker shade depicts normal alignment with the mechanical axis now bisecting the knee.

Not only is physeal growth inhibited, but also the Hueter-Volkmann effect is exerted upon the entire hemiepiphysis (lateral femoral condyle), preventing its normal expansion. According to the Hueter-Volkmann principle, continuous or excessive compressive forces on the epiphysis have an inhibitory effect on growth. Consequently, growth in the lateral condyle of the femur is suppressed globally, resulting in a shallow femoral sulcus and a propensity for the patella to tilt and subluxate laterally.

In children younger than 6 years, physiologic genu valgum is common but is self-limiting and innocuous. In children (of any age) with pathologic valgus, when the mechanical axis deviates into or beyond the lateral compartment of the knee, regardless of the etiology, a number of clinical problems may ensue.

Medial ligamentous strain may be associated with recurrent knee pain. The patellofemoral joint may become shallow, incongruous, or unstable, causing activity-related anterior knee pain. In extreme cases, frank patellar dislocation with or without osteochondral fractures may ensue. During gait, medial thrust of the tibia relative to the femur may compromise the integrity of the restraining medial collateral ligaments, resulting in localized pain and progressive joint laxity.

In addition to knee pain and laxity, patients may develop a circumduction gait, swinging each leg outward to avoid knocking their knees together. This gait pattern is awkward and laborious; the patient is unable to run, ride a bicycle, or participate safely and effectively in play or sports activities, potentially leading to social isolation and possible ridicule. Left untreated, the natural history for this condition is likely to be that of inexorable progression and deterioration.

Because patellar dislocation reflects an insidious and progressive growth disturbance, nonoperative management, relying on physical therapy and bracing, is of little value. During the adult years, premature and eccentric stress on the knee may result in hypoplasia of the lateral condyle, meniscal tears, articular cartilage attrition, and arthrosis of the anterior and lateral compartments.

The lifelong valgus knee presents a daunting challenge to the adult reconstructive orthopedist. Total knee arthroplasty may be fraught with complications, including persistent malalignment, neurovascular compromise, patellar instability, and premature loosening of the prosthetic components.

Despite the current availability of sex-specific total knee components, or patellofemoral arthroplasty, these anatomic problems continue to pose a challenge. Therefore, it is in the best interest of the patient for the clinician to try to prevent such an outcome. Correction of genu valgum and neutralization of the forces across the knee are the goals of early and, if necessary, repeated intervention, which forestalls the need for more invasive adult reconstructive procedures.

It is well recognized that toddlers aged 2-6 years may have physiologic genu valgum. For this age group, typical features include ligamentous laxity, symmetry, and lack of pain or functional limitations. Despite the sometimes-impressive deformities, no treatment is warranted for this self-limiting condition. Bracing is meddlesome and expensive, and shoe modifications are unwarranted. The natural history of this condition is benign; therefore, parents simply need to be educated as to what to expect and when. Annual follow-up until resolution may help to assuage their fears.

In contrast, adolescent idiopathic genu valgum is not benign or self-limiting. Teenagers may present with a circumduction gait, anterior knee pain, and, occasionally, patellofemoral instability. The natural history of this condition may culminate in premature degenerative changes in the patellofemoral joint and in the lateral compartment of the knee.

Various other conditions, including postaxial limb deficiencies, genetic disorders such as Down syndrome, hereditary multiple exostoses, neurofibromatosis, and vitamin D–resistant rickets may cause persistent and symptomatic genu valgum. Some of these conditions require team management with other health care providers; however, surgical intervention is still likely to be necessary to correct the malalignment of the knees.

Adolescent idiopathic genu valgum may be familial or it may occur sporadically. The true incidence is unknown. Certainly, it is one of the most common causes of anterior knee pain in teenagers and is a frequent reason for orthopedic consultation. Predisposing syndromes, such as hereditary multiple exostoses, Down syndrome, and skeletal dysplasias, are more apt to manifest in patients aged 3-10 years, and valgus may become severe if untreated. Whereas the angle may not change, as the height increases, the mechanical axis progressively shifts more laterally, manifested by increasing knee pain and/or patellar instability.

Regardless of the etiology, surgical correction of significant and symptomatic malalignment is warranted; when required in younger children, the process may have to be repeated as they continue to grow.

In countries where malnutrition is common and access to medical care is limited, the overall incidence of genu valgum is undoubtedly higher. Although polio has been largely eradicated, other infectious diseases may result in growth disturbances. Mistreated (or untreated) traumatic injuries cause physeal damage or overgrowth (for example), resulting in progressive and disabling clinical deformity. Likewise, untreated congenital anomalies, skeletal dysplasias, genetic disorders, metabolic conditions, and rheumatologic diseases may cause genu valgum.

Provided that the appropriate criteria (ie, sufficient growth remaining, careful analysis and preoperative planning, proper plate insertion, periodic follow-up) are met, the results of guided growth are uniformly gratifying. The parents and the surgeon must be patient, however, because growth is a slow process. The immediate satisfaction (carpentry) of osteotomies is supplanted by delayed gratification (gardening). The success of this technique is predicated on skillful harnessing of the inherent power of the growth plate. Even a sick physis can respond, given enough time; this is why the procedure works even in patients with skeletal dysplasias and vitamin D–resistant rickets.[1]

That patient and family satisfaction are excellent is not surprising, given that guided growth, compared with osteotomy, is less invasive, relatively painless, more cost-effective, and less risky. Minimal down time is associated with the procedure, and educational and recreational activities are only temporarily interrupted. Consequently, previous arbitrary guidelines pertaining to minimum age and diagnoses have been abandoned. In the author's opinion, guided growth with a tension band has become the treatment of choice for most angular deformities of the knee. Osteotomy can still be performed if guided growth is unsuccessful (or vice versa).

Wiemann et al compared the use of the eight-plate for hemiepiphysiodesis (n=24) with that of physeal stapling (n=39) in 63 cases of angular deformity in lower extremities. They found the eight-plate to be as effective as staple hemiepiphysiodesis in terms of the rate of correction (~10º/year) and the complication rate (12.8% vs 12.5%). However, patients with abnormal physes (eg, Blount disease, skeletal dysplasias) did have a higher rate of complications than those with normal physes (27.8% vs 6.7%), though there was no difference between the eight-plate group and the staple group.[2] We have not shared this experience; the complication rate is exceedingly low in both groups.[3]

After analyzing 35 patients, Jelinek et al reported a shorter operating time for implantation and explantation was noted for the eight-plate technique than for Blount stapling.[4]

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved