Subacute osteomyelitis is a distinct form of osteomyelitis, and Brodie abscess is one type of subacute osteomyelitis. Subacute osteomyelitis is difficult to diagnose because the characteristic signs and symptoms of the acute form of the disease are absent.[1, 2, 3] In noncontemporary literature, Brodie abscess was referred to as a chronic form of osteomyelitis; however, in almost all contemporary literature references, Brodie abscess is referred to as the most common type of the subacute form of osteomyelitis.

Sir Benjamin Brodie, a surgeon in St George's Hospital, London, United Kingdom, first described subacute osteomyelitis in 1832.[4] He amputated the leg of a man who had intractable pain for a number of years. On examination of the amputated limb, Brodie found a cavity the size of a walnut filled with dark-colored pus. The bone immediately surrounding the cavity was whiter and harder than the surrounding bone. The inner surface of the cavity appeared to be highly vascular.[4] Since then, low-grade pyogenic abscesses of the bone have frequently been referred to as Brodie abscesses.

In 1951, Wiles referred to Brodie abscesses as a particular form of chronic osteomyelitis that follows an acute attack, when the virulence of the organism and the resistance of the patient are evenly balanced.[5] Little discussion exists in the literature again until Harris and Kirkaldy-Willis described primary subacute osteomyelitis;[6] they were the first to publish a radiograph that demonstrated an abscess of subacute osteomyelitis crossing the epiphyseal plate of the distal tibia.

On the basis of their experience in East Africa, Harris and Kirkaldy-Willis classified primary subacute osteomyelitis, into two types, depending on whether a bone abscess is present or not, with the first type being metaphyseal and the second type diaphyseal. Gledhill classified subacute osteomyelitis according to radiologic appearance,[7] and this classification scheme was subsequently modified by Roberts et al.[8]

Subacute osteomyelitis is characterized by mild to moderate pain, usually described as a persistent ache; intermittent symptoms; insidious onset; and, often, a long delay between the onset of pain (the most common presenting symptom) and the diagnosis. Usually, symptoms are present for 2 weeks or longer. The course is generally marked by few or no constitutional symptoms and no known previous acute disease. A systemic reaction is absent, and supportive laboratory data are inconsistent. Subacute osteomyelitis may mimic various benign and malignant conditions, resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment. The most frequently made incorrect diagnosis is that of tumor.[1, 9, 10]

NextInterconnecting subacute osteomyelitis of the epiphysis and metaphysis is readily explainable in infants younger than 18 months, when one considers that vascular communication between the epiphysis and metaphysis is present until age 18 months, as described by Trueta.[11] Epiphyseal lesions may also occur in older adolescents when the growth plate becomes attenuated and fails to provide a barrier to epiphyseal infection. Another interesting explanation for the localization of subacute osteomyelitis adjacent to the growth plate cartilage is the finding by Speers and Nade that Staphylococcus aureus has a certain affinity for physeal cartilage.[12]

The transgression of the epiphyseal plate from osteomyelitis foci has been well documented (see the images below). A review of the literature indicates that despite localized transgression of the epiphyseal plate by subacute osteomyelitis, growth plate arrest, stimulation, or development of transepiphyseal bony bars is exceedingly rare.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the distal tibia. This image depicts an eccentrically located radiolucent lesion crossing the epiphyseal plate, type IIIb.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the distal tibia. This image depicts an eccentrically located radiolucent lesion crossing the epiphyseal plate, type IIIb.

Lateral radiograph of the distal tibia. This image depicts an eccentrically located radiolucent lesion crossing the epiphyseal plate, type IIIb.

Lateral radiograph of the distal tibia. This image depicts an eccentrically located radiolucent lesion crossing the epiphyseal plate, type IIIb.

Subacute osteomyelitis occurs in a much wider variety of bones than does the acute type, and the disease occurs at various sites within the affected bones. The lower limb is affected much more often than the upper limb, and the tibia is affected relatively more often than is the femur.[13, 14] Subacute osteomyelitis may involve only the epiphysis, which is contrary to the belief that primary bone infection does not occur in the epiphysis (see the image below).

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the distal femur. These images depict a type IIIa epiphyseal lesion.

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the distal femur. These images depict a type IIIa epiphyseal lesion.

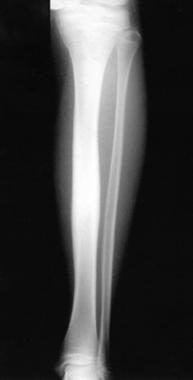

The diaphysis is occasionally affected (see the first and second images below), though this occurs more often in adults than in children; the most commonly affected site is the metaphysis (see the third and fourth images below).

Anteroposterior radiograph of the left tibia. This image depicts periosteal reaction of the diaphyseal cortex, type IIb.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the left tibia. This image depicts periosteal reaction of the diaphyseal cortex, type IIb.

Lateral radiograph of the left tibia. This image depicts periosteal reaction of the diaphyseal cortex, type IIb.

Lateral radiograph of the left tibia. This image depicts periosteal reaction of the diaphyseal cortex, type IIb.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the distal radius. This image depicts a central metaphyseal lesion (punched-out radiolucency), type Ia.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the distal radius. This image depicts a central metaphyseal lesion (punched-out radiolucency), type Ia.

Lateral radiograph of the distal radius. This image depicts a central metaphyseal lesion (punched-out radiolucency), type Ia.

Lateral radiograph of the distal radius. This image depicts a central metaphyseal lesion (punched-out radiolucency), type Ia.

Communication of the lesion between the metaphysis and the epiphysis is also common (see the images below).

Anteroposterior radiograph of the distal tibia. This image depicts an eccentrically located radiolucent lesion crossing the epiphyseal plate, type IIIb.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the distal tibia. This image depicts an eccentrically located radiolucent lesion crossing the epiphyseal plate, type IIIb.

Lateral radiograph of the distal tibia. This image depicts an eccentrically located radiolucent lesion crossing the epiphyseal plate, type IIIb.

Lateral radiograph of the distal tibia. This image depicts an eccentrically located radiolucent lesion crossing the epiphyseal plate, type IIIb.

Other sites in which subacute osteomyelitis is frequently reported are metaphyseal-equivalent locations, such as the pelvis, the vertebrae, the calcaneum, the clavicle, and the talus. When subacute osteomyelitis occurs in tarsal bones, it usually occurs in the subchondral part or on the border of the apophysis of the calcaneus. Subacute lesions of the spine occur more often in adults than in children (see the image below).

Lateral radiograph of the lumbosacral spine. This image depicts destruction of bone and disc space, type IVa.

Lateral radiograph of the lumbosacral spine. This image depicts destruction of bone and disc space, type IVa.

When subacute osteomyelitis occurs in the long bones of adults, the diaphysis is involved as often as is the metaphysis. The patella is rarely involved. Multifocal subacute osteomyelitis is a rare form of subacute osteomyelitis that was reported by Season and Miller and by Rasool.[15, 16] It is usually associated with a deficient immune system.

Subacute osteomyelitis is one of the many clinical presentations of hematogenous osteomyelitis. The organisms reach the bone from a disrupted site elsewhere in the body that may pose little or no threat of its own accord (eg, skin pustule, furuncles, impetigo, infected blisters and burns). Infection has even been suggested to be the outcome of common events such as normally harmless daily teeth brushing.

The causative organism is usually coagulase-positive Staphylococcus (30-60%). Other organisms encountered are Streptococcus, Pseudomonas, Haemophilus influenzae (much less common after widespread vaccination), and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. An increased prevalence of Kingella kingae, a gram-negative coccobacillus, was noted by Lundy and Kehl, mostly in children younger than 3 years as a cause of all types of osteoarticular infections, including subacute osteomyelitis.[17]

Dartnell et al in their systematic review confirmed that S aureus is the most common organism detected. They also noted that the isolation of K kingae is increasing.[14]

Patients with sickle cell anemia are predisposed to infections with Salmonella, whereas Pseudomonas aeruginosa is isolated from skeletally mature intravenous drug abusers. However, in almost 25-50% of cases of subacute osteomyelitis, no organism is cultured.[18]

Factors that may influence the behavior of a septic process in bone include the following:

Moreover, subacute osteomyelitis appears to depend on the interplay between the infecting bacteria and the immune mechanism of the host. True primary subacute osteomyelitis represents a favorable host-pathogen response. In East Africa, where subacute osteomyelitis is the most common form of osteomyelitis, children in bare feet have frequent foot infections and develop a high resistance to staphylococcal infections, as pointed out by Harris and Kirkaldy-Willis.[6]

That trauma results in vascular injury and an area of hypoxia in the metaphyseal region of bone is an attractive theory, but it is difficult to prove as an inciting cause of subacute osteomyelitis. When the host resistance is insufficient to overwhelm the infection, it is conceivable that subacute osteomyelitis may develop.

The pyogenic organisms' initial attack is presumed to be controlled by the host, and presumably, spread to large areas of cancellous tissue or to the subperiosteal region has not occurred. A central area of suppurative necrosis in the metaphyseal region becomes enclosed by a wall of fibrous tissue and granulations, the offending organisms are destroyed, and the pus is usually sterile.

The circulation of the epiphysis predisposes to sluggish blood flow through the vascular loops. Possibly, the rich supply of the reticuloendothelial cells located in the epiphysis attenuates the osteomyelitis, leading to the subacute course in this region.

The metaphyseal-equivalent regions are defined as the portion of a flat or irregular bone that borders cartilage (apophyseal growth plates, articular cartilage, or fibrocartilage), such as the pelvis, the vertebrae, the clavicle, and the small bones (tarsal bones).[19] The vascular anatomy and the mechanism of seeding are analogous to those found in the metaphysis of long bones.

The incidence of subacute osteomyelitis has increased since antibiotics have been used to treat osteomyelitis. The disease reportedly accounts for 2.4%,[20] 8.8%,[21] 35%,[22] and 42%[23] of primary bone infections, though a report by Blyth et al indicates a mild decline in the incidence of both acute and subacute osteomyelitis, with greater decline in the acute form than in the subacute form.[24] In East Africa, subacute osteomyelitis is the most common form of osteomyelitis.

Onset of subacute osteomyelitis tends to occur in slightly older children than the onset of acute osteomyelitis. Subacute osteomyelitis has been reported in patients as young as 6 months and as old as 39 years, but the common age range is 2-15 years. Sex ratios vary, but in general, males are affected slightly more often than are females.

Subacute osteomyelitis is difficult to diagnose, but once diagnosed, it is a curable disease with a 100% cure rate. Hamdy et al reported their results in treating 44 patients[25] of which 24 were treated with antibiotics only, and 20 had surgical debridement followed by antibiotics. With the exception of one patient who received inadequate antibiotic therapy, all patients responded well, regardless of whether treatment was conservative or surgical. At an average follow-up of 18 months, no recurrences and no damage to the physis were reported.[25, 26]

No good outcome studies have been reported as of yet, but from the available literature (apart from the previously mentioned rare complications), the outcome of subacute osteomyelitis is excellent, and full recovery is the rule in most cases.

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved