Intercondylar eminence fractures were first described by Poncet in 1875. In 1959, Meyers and McKeever surgically addressed only type III fractures.[1] Since then, techniques have improved and awareness of the importance of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) integrity has increased. Currently, many authorities recommend anatomic reduction and fixation for fractures displaced to any noticeable degree, including type II fractures.

Fractures of the tibial intercondylar eminence are observed mostly in children and adolescents, often after minimal trauma; good results are expected with treatment by anatomic reduction. Although adults also can sustain this type of injury, they will often have additional concurrent knee trauma and, despite anatomic reduction, frequently do poorly.

The future of surgical management of displaced intercondylar eminence fractures is the arthroscopic approach. As arthroscopic skills advance, the need for an arthrotomy to fix these types of fractures will decrease. Another future direction is the use of bioabsorbable implants for fixation of such injuries, which would provide rigid fixation but eliminate the need for hardware removal.

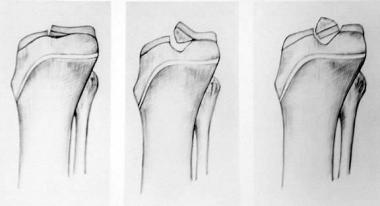

Intercondylar eminence fractrues are commonly classifed according to the Meyers and McKeever classification system (see the image below) as follows:

Meyers and McKeever classification of type I, II, and III intercondylar eminence fracture injuries.

Meyers and McKeever classification of type I, II, and III intercondylar eminence fracture injuries.

Zaricznyj proposed another category, type IV fractures (displacement with a comminuted avulsed fragment).[2]

NextThe tibial eminence consists of the eminent confluence of the tibial plateaus and contains two spines. The medial spine serves as the attachment of the ACL. The ACL, which has a broad insertion onto the tibial eminence, fans out and coalesces with the attaching fibers of the anterior horn of the medial meniscus anteriorly and the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus posteriorly. These meniscal attachments or the transverse intermeniscal ligament may be interposed between the fracture and its bed, thereby blocking a reduction, though this is controversial.[3, 4]

Anterior displacement of the tibia on the femur (often with a rotational component) leads to stress through the ACL, which causes failure at the incompletely ossified tibial eminence before the ligament itself fails. Some controversy exists as to whether microtearing of the ACL is associated with an intercondylar eminence fracture and results in ACL laxity despite anatomic fixation of the fracture.[5]

Intercondylar eminence fractures can extend into either of the articular tibial plateaus. Associated meniscal or ligamentous injuries, such as a medial collateral ligament tear, also are possible. These types of complicating injuries are more often observed in adults, who frequently sustain higher-energy trauma (ie, injuries involving a large amount of kinetic energy, such as those sustained in motor vehicle accidents).

Intercondylar eminence fractures in skeletally immature patients usually result from injuries that would cause ACL tears in skeletally mature patients. Meyers and McKeever reported that a large number of bicycle falls produce this type of injury in children.[1] However, intercondylar eminence fractures can be caused by a spectrum of sporting activities and by motor vehicle accidents.

Determining the exact frequency of intercondylar eminence fractures is difficult. These injuries were initially believed to be rare; however, their incidence appears to be rising, possibly in part because of a greater awareness of the condition among physicians. The rising incidence may also be related to an increase in sporting activities in early adolescence.

Most studies report good results from the use of open or arthroscopic reduction and fixation of displaced intercondylar eminence fractures, or, in the case of minimal displacement, from the employment of closed treatment.[6] Although some studies have demonstrated an increased treatment-related ACL laxity by objective measures, these results do not correlate with patients' symptoms.

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved