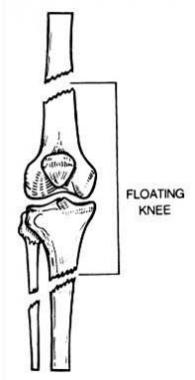

Floating knee is a flail knee joint resulting from fractures of the shafts or adjacent metaphyses of the femur and ipsilateral tibia (see image below). Floating knee injuries may include a combination of diaphyseal, metaphyseal, and intra-articular fractures.[1] This combination of fractures is less common in the pediatric population than in adults. However, epiphyseal injury can adversely affect open growth plates, predisposing a child to limb-length discrepancy and angular deformities.

Floating knee injury.

Floating knee injury.

Blake and McBryde initially described this injury, which is generally caused by high-energy trauma. Local trauma to the soft tissues is often extensive, and life-threatening injuries to the head, chest, or abdomen may also be present.[2]

An initial evaluation to determine the extent of a patient's injuries is of critical importance. This evaluation should be followed by an appropriate sequence of emergency diagnostic and therapeutic measures.

Rates of infection, nonunion, malunion, and stiffness of the knee are relatively high. These complications can lead to functional impairment and frequently cause unsatisfactory results.

NextLittle is recorded in the English-language literature on the subject of ipsilateral fracture of the femur and tibia. The complication rate associated with floating knee injuries remains high, regardless of the treatment regimen used.

This severe injury appears to be increasing in frequency. A male preponderance is observed, particularly in young adults 20-30 years of age.

Road traffic accidents are the most common mechanisms of trauma, followed by gunshot wounds and falls from heights.

Floating knee injuries must be included in assessment and treatment protocols for patients with polytrauma.

Damage to the vessels (mainly the popliteal and posterior tibial arteries) and lesions of the nerves (eg, peroneal nerve) are common. Vascular injury is common and may be limb threatening if not recognized and addressed. Often, the vascular injury is to the anterior tibial artery and does not result in ischemia and is not treated with vascular repair or reconstruction. However, vascular status needs to be assessed and addressed as appropriate. Traction usually causes neurapraxia, which often resolves, but complete resolution cannot always be anticipated.

The incidence of open fractures is high, approaching 50-70%, at 1 or both fracture sites. The most common combination is a closed femoral fracture with an open tibial fracture.

A well-documented finding is injury to the knee ligaments that occur in association with ipsilateral femoral and tibial fractures. Anterolateral rotatory instability is the most common pattern of instability. Knee ligament injury is not always suspected, and joint swelling due to hemarthrosis should not be mistaken for a sympathetic effusion. The ipsilateral femoral and tibial shaft fractures and knee ligament injury appear to be part of a continuum of combined injuries resulting from complex, high-energy forces.[3]

In skeletally immature patients, floating knee is uncommon. Few studies of this injury have been conducted in children. Data from available studies show that findings observed in children are comparable to those in adults in terms of the mechanism of fracture, the incidence of associated major injuries, and the complexity of treatment.

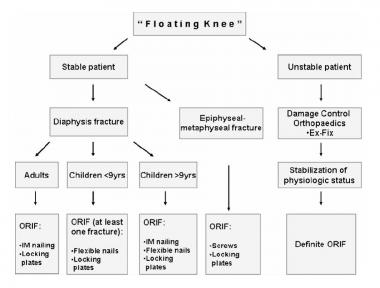

In adults, all floating knee injuries must be addressed with early anatomic reconstruction and stable surgical stabilization of both fractures. The goal is to allow for early joint mobilization.

In children, especially those younger than 10 years, treatment of ipsilateral femoral and tibial fractures is controversial.

The treatment protocol for floating knee injuries is summarized in the image below.

Treatment protocol for floating knee injuries. Ex-Fix = external fixation; IM = intramedullary; ORIF = open reduction and internal fixation.

Workup

Treatment protocol for floating knee injuries. Ex-Fix = external fixation; IM = intramedullary; ORIF = open reduction and internal fixation.

Workup

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved