In trigger finger (TF), one of the most common causes of hand pain and disability, the flexor tendon causes painful popping or snapping as the patient flexes and extends the digit. The patient may present with a digit locked in a particular position, most often flexion, which may require gentle, passive manipulation into full extension.[1] See the image below.

Trigger finger often results in difficulty flexing or (in this case) extending metacarpophalangeal joint of involved digit.

Trigger finger often results in difficulty flexing or (in this case) extending metacarpophalangeal joint of involved digit.

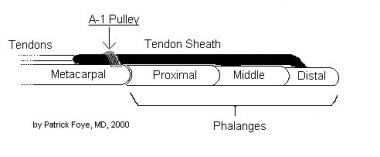

TF results from thickening of the flexor tendon within the distal aspect of the palm.[2, 3] This thickening causes abnormal gliding and locking of the tendon within the tendon sheath. Specifically, the affected tendon is caught at the edge of the first annular (A1) pulley.

Signs and symptoms of TF are as follows:

Children with trigger thumb rarely complain of pain. They usually are brought in for evaluation when aged 1-4 years, when the parent first notices a flexed posture of the thumb’s interphalangeal (IP) joint. These children often demonstrate bilateral fixed flexion contractures of the thumb by the time they present to the physician.[4] By the time the child presents to the clinic, surgical treatment is already indicated in most instances.

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

As a rule, no lab tests are needed in the diagnosis of TF. If there is a concern regarding an associated, undiagnosed condition, such as diabetes mellitus (DM), RA, or another connective tissue disease, tests such as those assessing glycosylated hemoglobin (HgbA1c), fasting blood sugar, or rheumatoid factor should be ordered.

Radiography rarely is indicated in TF.[5] Hand radiographs are performed only if abnormal pathology (eg, abnormal sesamoids, loose bodies in the MCP joint, osteoarthritic spurs on the metacarpal head, avulsion injuries of collateral ligaments) is suspected.

See Workup for more detail.

Conservative treatment

Corticosteroid injection in the area of tendon sheath thickening is considered to be the first-line treatment of choice for TF. Custom-made splinting of the MCP joint, albeit rarely used, is another conservative treatment, used in patients who do not wish to undergo a steroid injection or as an adjuvant to injection. Typically, a custom-made splint is used to hold the MCP joint of the involved finger at 10-15° of flexion, leaving the PIP and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints free.

Surgery

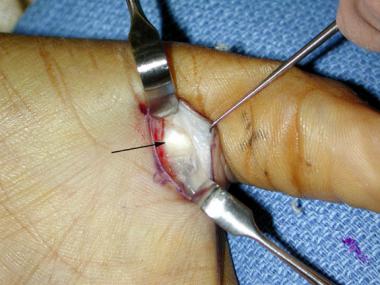

Trigger digits that fail to respond to 2 injections usually require surgical treatment, in the form of surgical release of the A1 pulley, under local anesthesia. During the procedure, the proximal edge of the A1 pulley is identified, and a scalpel blade is used to divide the entire A1 pulley in the midline under vision. Dissection of the nodule in the tendon is rarely indicated and may actually cause tendon weakening or rupture. With relief of triggering and friction following the release of the A1 pulley, the nodule usually regresses in size.

If a percutaneous approach is favored, a pair of blunt-tipped, fine scissors is introduced through the incision, and the A1 pulley is transected.

The open technique is absolutely essential for the thumb or little finger or in the presence of PIP contractures. Percutaneous release should be reserved for the index, middle, and ring fingers.[6, 7, 8, 9]

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

NextTrigger finger (TF) is one of the most common upper limb problems to be encountered in orthopedic practice and is also one of the most common causes of hand pain and disability. It results from thickening of the flexor tendon within the distal aspect of the palm.[2, 3] This thickening causes abnormal gliding of the tendon within the tendon sheath. Specifically, the affected tendon is caught at the edge of the first annular (A1) pulley. (See Etiology and Pathophysiology.)

Patients can have difficulty flexing the affected digit if the tendon is caught distal to the A1 pulley, or extending the digit if the tendon is caught proximal to the pulley. The condition is very painful, especially when the locked digit snaps (releases) beyond the restriction by the use of increased force.

The etiology of TF remains unknown or uncertain, although triggering seems to occur more frequently in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or diabetes mellitus (DM). (See Etiology and Pathophysiology.)

TF begins as discomfort in the palm during movements of the involved digit(s). Gradually or, in some cases, acutely, the flexor tendon causes painful popping or snapping as the patient flexes and extends the digit. The patient may present with a digit locked in a particular position, most often flexion, which may require gentle, passive manipulation into full extension. (See Presentation.)[1]

TF has a predilection for the dominant hand, with the most commonly affected digit being the thumb, followed by the ring, long, little, and index fingers. (However, a retrospective study of 577 TFs by Schubert et al found no relation to hand dominance.[10] ) The involvement of several fingers is not unusual.

TF occurs much less frequently in the pediatric population than in adults and develops almost exclusively in the thumb.[11] Historically, the condition in children has been referred to as congenital trigger thumb.[12] Evidence indicates, however, that it usually presents sometime after infancy and is thus more appropriately referred to as pediatric trigger thumb. (See Epidemiology and Presentation.)[13] Yet, by the time medical opinion is sought, surgery is usually indicated.

In the past, triggering of the digits was treated by splinting in extension, which caused stiffness and, consequently, loss of metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal flexion. Due to dissatisfaction with this form of treatment, researchers used intrasheath steroid injections instead, which resulted in a high proportion of good results. (See Treatment and Medication.)[14, 10]

In an uncomplicated case of trigger digit, the first-line therapy is still generally agreed to be injection into the tendon sheath, with surgical release of the A1 pulley as second-line treatment.

Surgery, in the form of release of the A1 pulley, became popular when splinting and/or injection therapy failed or in the presence of other pathology, such as RA, in which injection treatment proved futile or there was a risk of tendon rupture or infection.

Tendon sheaths of the long flexors run from the level of the metacarpal heads (distal palmar crease, superficial; volar plate, deep) to the distal phalanges. They are attached to the underlying bones and volar plates, which prevent the tendons from bowstringing. Predictable and efficient thickenings in the fibrous flexor sheath act as pulleys, directing the sliding movements of the fingers.

The two types of pulleys are annular (A) and cruciate (C). Annular pulleys are composed of single fibrous bands (ie, rings), while cruciate pulleys have two crossing fibrous bands.

The order of the pulleys from proximal to distal is as follows:

Flexor tendons pass within tendon sheath and beneath A1 pulley at approximately metacarpal head, beyond which they travel into digit.

Flexor tendons pass within tendon sheath and beneath A1 pulley at approximately metacarpal head, beyond which they travel into digit.

The A2 and A4 pulleys are vital in preventing bowstringing of the flexor tendons and must be preserved or reconstructed after any damage to them.

The flexor anatomy of the thumb differs from that of the fingers. The flexor pollicis longus (FPL) tendon is a single tendon within the flexor sheath that inserts onto the base of the distal phalanx. The fibro-osseous sheath is composed of two annular pulleys (A1 and A2) that arise from the palmar plates of the MCP and interphalangeal (IP) joints, respectively. The oblique pulley, which originates from and inserts onto the proximal phalanx, is the most important pulley from a biomechanical perspective. The oblique pulley is approximately 10 mm in length, blending with a portion of the adductor pollicis insertion.

The digital nerves and arteries run parallel to the tendon sheath distally. At the level of the MCP flexion crease, they lie just deep to the skin. Proximal to the A1 pulley, the radial digital nerve of the thumb crosses obliquely over the sheath.

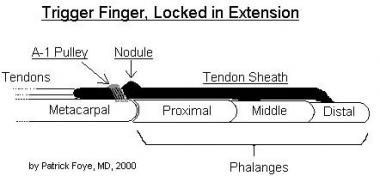

A mismatch between the flexor tendon and the proximal pulley mechanism occurs in most cases of TF. Normally, the tendons of the finger flexors glide back and forth under a restraining pulley.[15, 16, 17] Thickening of the flexor tendon sheath restricts the normal gliding mechanism. A nodule may develop on the tendon, causing the tendon to get stuck at the proximal edge of the A1 pulley when the patient is attempting to extend the digit, thereby causing difficulty. (See the image below.)

Inflamed nodule can restrict tendon from passing smoothly beneath A1 pulley. If nodule is distal to A1 pulley (as shown in this sketch), then digit may get stuck in extended position. Conversely, if nodule is proximal to A1 pulley, then patient's digit is more likely to become stuck in flexed position.

Inflamed nodule can restrict tendon from passing smoothly beneath A1 pulley. If nodule is distal to A1 pulley (as shown in this sketch), then digit may get stuck in extended position. Conversely, if nodule is proximal to A1 pulley, then patient's digit is more likely to become stuck in flexed position.

When more forceful attempts are made to extend the digit, by using increased force from the finger extensors or by applying an external force (for example, by exerting force on the finger with the other hand), the digit classically snaps open with significant pain at the distal palm and into the proximal aspect of the affected digit. Less commonly, the nodule is restricted distal to the A1 pulley, resulting in difficulty flexing the digit.

Using sonoelastography, a newer technique for quantitative assessment of the stiffness of soft tissues, the data from one study noted that the causes for snapping in trigger finger were increased stiffness and thickening of the A1 pulley. Three weeks after corticosteroid injection, the pulley thickness and the ratio of subcutaneous fat to the pulley both decreased; snapping disappeared in all patients studied.[18]

The etiology of TF is unknown or uncertain. It is suspected that nodule formation in the tendon, morphologic changes in the pulley, or both in combination may effect triggering, though why these changes are actually initiated remains unknown.

Several studies have demonstrated a correlation between TF and activities that require exertion of pressure in the palm while a powerful grip is used or that involve repetitive, forceful digital flexion (eg, arc welding, use of heavy shears). Proximal phalangeal flexion in power-grip activities causes high annular loads at the distal edge of the A1 pulley. Hueston and Wilson have suggested that bunching of the interwoven tendon fibers causes the reactive intratendinous nodule observed at surgery.[19]

Thus, in conclusion, the exact etiology remains unknown, but certain conditions such as diabetes mellitus (DM) or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) may predispose an individual to triggering of the digit.

Sampson et al concluded that the underlying pathobiologic mechanism for triggering is fibrocartilaginous metaplasia of the pulleys due to trauma or disease.[20] Several studies have failed to demonstrate the presence of acute or chronic inflammatory cells within the tenosynovium. The suffix -itis in the term stenosing tendovaginitis actually is a misnomer unless the condition is associated with RA or inflammatory arthritis.

The exact etiology is still unknown, but it is thought that DM or autoimmune conditions may contribute to morphological changes in the pulley and/or the tendon sheath to cause triggering. Systemic causes of TF are collagen-vascular diseases, including the following[21] :

Septic causes of TF are secondary infections (eg, tuberculosis). A few case reports have documented rare causes of TF, including tenosynovitis that itself resulted from a Mycobacterium kansasii infection in an immunocompetent patient; triggering following the development of calcific tendonitis has been reported in a child. Such cases should invoke a high degree of suspicion.

The association of idiopathic TF with idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome has long been suggested. A study of 551 patients with no predisposing causes diagnosed with either TF, carpal tunnel syndrome, or both based on clinical grounds reported that 43% of patients with TF also had concomitant carpal tunnel syndrome; this is significantly higher than the population prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome, which is about 4%.[22]

A retrospective study by Grandizio et al indicated that the risk of developing TF following surgical carpal tunnel release is greater in patients with DM than in those without DM. In the study, the investigators found that out of 1003 carpal tunnel releases in patients without DM, the incidence of TF at 6 and 12 months was 3% and 4%, respectively, whereas out of 214 carpal tunnel releases in patients with DM, the incidence at 6 and 12 months was 8% and 10%, respectively. The severity of the DM, however, was not found to be a significant factor in the development of TF.[23]

Trigger thumb (see the image below) usually occurs idiopathically, though it develops more frequently in individuals with diabetes or osteoarthritis. Trigger thumb is more likely to occur in an individual with any condition that causes diffuse proliferation of the tenosynovium, such as inflammatory arthritis, gout, or chronic infection (eg, fungus, atypical mycobacteria). This process can extend distal to the MCP joint and, when severe, cause stiffness rather than intermittent triggering.

Trigger thumb. A1 pulley exposed within surgical field (arrow). Digital neurovascular bundles behind retractors.

Trigger thumb. A1 pulley exposed within surgical field (arrow). Digital neurovascular bundles behind retractors.

Certain people appear more prone to tenosynovitic conditions; patients with trigger thumb are more likely to develop carpal tunnel syndrome and de Quervain disease. The roles of overuse and trauma in trigger thumb are controversial, though the condition does have a predilection for the dominant hand.

TF is a relatively common condition and occurs two to six times more frequently in women than in men.

Several series found the peak incidence of trigger digit to be in individuals aged 55-60 years. Age distribution has not changed significantly despite an increase in computing activities and repetitive tasks. As previously mentioned, TF in the pediatric population occurs much less frequently than in adults and develops almost exclusively in the thumb.[11]

The prognosis in TF is very good; most patients respond to corticosteroid injection with or without associated splinting. Some cases of TF may resolve spontaneously and then reoccur without obvious correlation with treatment or exacerbating factors.

Freiberg et al found a greater success rate for TF injection therapy when the treatment was used in patients in whom an examiner could palpate a discrete, rather than a diffuse, nodular consistency in the flexor sheath.[24] Digits with a discrete, palpable nodule had a 93% success rate with a single injection of triamcinolone at 3 months' follow-up, whereas digits with a diffuse pattern had a 52% failure rate.

Marks and Gunther reported an 84% success rate in trigger digits and a 92% success rate in trigger thumbs following a single injection of triamcinolone.[14]

Using sonoelastography, a newer technique for quantitative assessment of the stiffness of soft tissues, one group noted that the causes for snapping in trigger finger were increased stiffness and thickening of the A1 pulley. Three weeks after corticosteroid injection, the pulley thickness and the ratio of subcutaneous fat to the pulley both decreased; snapping disappeared in all patients studied.[18]

Griggs and co-investigators reported an overall success rate of 50% for steroid injection in patients with DM.[25] Patients with insulin-dependent diabetes had a higher incidence of multiple digit involvement and required surgical release more frequently than did patients who were not insulin dependent.[26, 27]

Patients who need surgical release generally have a very good outcome. Percutaneous TF release has been reported by several authors to be safe and efficacious, with success rates of 74-94% and no complications having been found at medium-term follow-up. The procedure is advised for individuals with established primary TF who have symptoms lasting longer than 4 months or for patients in whom injection therapy has failed to relieve symptoms. It is considered a reasonable choice following 1 injection failure and actually may confer cost benefits through permanent relief.

The prognosis is also very good for congenital trigger thumb that is treated with resection of the tendon nodule.

A study suggests that perioperative characteristics and outcomes differ between TF and trigger thumb and that the surgical outcome is poorer for TF than for trigger thumb (partly due to flexion contracture of the PIP joint).[28]

Triggering may resolve spontaneously in 23-63% of pediatric cases. If patients are not treated by the time they are aged 4 years, some may be left with permanent flexion contractures. Surgical release of the A1 pulley prior to this age leads to excellent results.[29, 30, 9]

As with patient education following any local injection, patients should be told to watch for signs and symptoms of infection and bleeding. Any suggestion of infection or excessive bleeding should be reported to the physician immediately.

Patients should understand that some increased tenderness may be noted at the injection site for 2-4 days, until the corticosteroid begins to have a significant therapeutic effect. If there is an inordinate amount of pain after the procedure, patients should contact the physician who performed the injection.

Patients should understand that a certain amount of numbness in the digit may occur if some of the local anesthetic has come into contact with a digital nerve; however, the numbness should resolve within a matter of hours after the injection. Significant, persistent numbness should be reported to the physician who performed the injection.

To minimize the risk of tendon rupture after corticosteroid injection, the patient should be advised that for a few weeks after the injection, he or she should avoid using the injected structures for excessively strenuous or forceful activity.

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved