The term mallet finger has long been used to describe the deformity produced by disruption of the terminal extensor mechanism at the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint.[1, 2, 3, 4] It is the most common closed tendon injury seen in athletes, though it is also common in nonathletes after "innocent" trauma. Mallet finger has also been referred to as drop, hammer, or baseball finger (though baseball accounts for only a small percentage of such injuries). (See Etiology and Epidemiology.)

The terminal portion of the extensor mechanism that crosses the DIP joint in the midline dorsally is responsible for active extension of the distal joint. A flexion force on the tip of the extended finger jolts the DIP joint into flexion. This may result in a stretching or tearing of the tendon substance or an avulsion of the tendon's insertion on the dorsal lip of the distal phalanx base. In either instance, active extension power of the DIP joint is lost, and the joint rests in an abnormally flexed position. (See Etiology and Presentation.)

Although athletes and coaches often believe mallet injuries to be minor, with many cases going untreated, all individuals with finger injuries, including suspected mallet finger, should have a systematic evaluation performed. Good results can usually be obtained with early treatment of such injuries, whereas a delay in or lack of treatment may produce permanent disability. (See Prognosis, Workup, and Treatment.)

Controversy exists as to whether the management of bony mallet injuries should be closed or open, especially when the dorsal avulsion fragment is large and the substance of the distal phalanx is subluxed anteriorly. The literature, however, supports the concept of nonoperative treatment even in these cases. (See Treatment.)

For patient education information, see the First Aid and Injuries Center, as well as Mallet Finger and Broken Finger.

NextThe terminal extensor tendon is a thin, flat structure measuring approximately 1 mm thick and 4-5 mm wide. This tendon occupies the sparse space between the bone and dorsal skin and inserts onto the dorsal lip of the distal phalanx, well proximal to the germinal nail matrix. At the DIP joint, the tendon's excursion is only several millimeters from full joint extension to 80° of flexion. As its name implies, the terminal extensor tendon is the terminal extension of the dorsal mechanism, which is a complex crossing of fibers at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints.

Powered by the lumbrical and interosseous muscles, the dorsal mechanism flexes the MCP joint and extends the PIP and DIP joints.

Any forced flexion of the finger while it is held in an extended position risks the integrity of the extensor mechanism at the DIP joint. The classic mechanism of injury is a finger held rigidly in extension or nearly full extension when the finger is struck on the tip by a softball, volleyball, or basketball. Other common mechanisms of injury include forcefully tucking in a bedspread or slipcover or pushing off a sock with extended fingers. A direct blow over the dorsum of the DIP joint may also produce mallet finger.

Mallet deformity can also be associated with a fracture of the dorsal articular surface of the distal phalanx. Radiographically, these bony avulsions can be characterized into three common patterns, as follows:

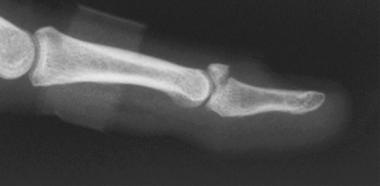

Generally, fleck fractures and nondisplaced avulsions that involve up to 40% of the joint surface are believed to be stable injuries.[2] Individuals with stable injuries are candidates for conservative treatment. (See the image below.)

Stable mallet fracture that involves 40% of the joint surface.

Stable mallet fracture that involves 40% of the joint surface.

From experimental studies, the rate of loading determines whether a tendon (or ligament) ruptures in midsubstance or is avulsed from its bony attachment. Rapid loading rates are more likely to cause a tear in the tendon itself, while lower loading rates are more likely to cause a bony avulsion. This is because the bone is relatively more viscoelastic than the tendon.

With a disruption of the dorsal mechanism at the DIP joint, the entire power of extension is directed to the PIP joint. Over time, and especially if the volar plate is lax, this concentrated extension force results in PIP joint hyperextension and a swan-neck deformity (ie, the DIP joint rests in an abnormally flexed position and the PIP joint rests in a hyperextended position). This deformity frequently causes a functional deficit.[5] Therefore, even if a mallet finger is not particularly symptomatic from a functional or cosmetic perspective, treatment of the mallet injury may preclude development of swan-neck deformity.

Several different athletic injuries can occur at the interphalangeal joints. The most common injury is a sprain of the PIP joint, the so-called jammed finger. Mallet fingers are less common than PIP joint sprains, but they are more common than PIP fractures or fracture dislocations and are also the most common closed tendon injury seen in athletes. (Similar injuries to the extensor mechanism at the interphalangeal joint of the thumb occur, albeit infrequently.) As previously stated, mallet finger is also a common trauma injury in nonathletes.

An untreated mallet finger is rarely of functional consequence unless a secondary swan-neck deformity occurs. Even in those cases, patients rarely request surgical reconstruction, choosing instead to live with the injury. With this in mind, treatment of a mallet finger should not be worse than the disease. Although an untreated mallet finger may be of some cosmetic consequence, treatment that leaves a finger with improved appearance but diminished function is not ideal.

A functionally and cosmetically normal finger can be obtained with conservative treatment, as long as the patient understands the concept of nonstop extension splinting and is compliant with the care. It may take several months following completion of splinting for local swelling and erythema to subside, but thereafter, the finger’s appearance and mobility will be excellent.

Frequently, a faint residual extension lag is present, in the range of 5-10°, but is observable only on close scrutiny. Beware of the patient with naturally hyperextensible interphalangeal joints. Caution these patients at the outset that the best they can hope for is restoration of extension to neutral rather than the degree of active hyperextension observed in their adjacent digits. This loss of complete extension will present no functional difficulties and will be of trivial cosmetic consequence.

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved