Flexor tenolysis is a surgical procedure used to remove adhesions that inhibit active flexion of digits.

NextWritten descriptions of procedures resembling tendon repair date back thousands of years to Ancient Rome, but more recently, flexor tenolysis has been adequately described in literature since the mid 20th century.[1, 2]

Normal active tendon function requires that flexor tendons be able to glide smoothly within their tendon sheath. Damage to these tendons can require surgical repair, and in spite of successful surgical tendon repair, postoperative management, and compliant physical therapy, tendon adhesions can develop.[3] Adhesions occur when during the healing process, scar tissue develops that connects tendons to the surrounding tendon sheath, thereby impeding normal tendon function.[4]

A 2012 study looked at a population of New York state dwellers who had flexor tendon reconstruction and found that 6% of patients required a subsequent surgical correction. Tenolysis was performed in 186 (3.6%) of 5229 patients, and tenolysis in combination with tendon re-repair was performed in 11 (0.2%) of 5229 patients.[5] In that particular population, patients who underwent concomitant nerve repair during the initial tendon repair were 26% less likely to undergo a reoperation.[5] Other studies have shown that approximately 28% of flexor tendon repairs have a suboptimal recovery period, likely due in large part to tendon adhesions.[6]

The exact etiology of tendon adhesions following surgery is unclear, but it appears to be due to scarring between the damaged surfaces of both the tendon and tendon sheath when the tendon is immobilized.[4]

The classical paradigm including inflammation, proliferation, synthesis, and apoptosis appears to be at work, but cellular activity has been shown to be greater in the surrounding tendon sheath.[2] Initially, the adhesions were thought to be the source of reparative cells, nutrients, and blood supply to the tendon, but that opinion has since fallen out of favor.[7] Subsequent investigations revealed that healing of tendons could occur in the absence of tendon adhesions and thereby helped to elucidate the presence of a population of cells inside the tendon capable of repair.[8] As far back as the 1960s, tendon immobilization was shown to be critical to adhesion formation.[9, 10] More recent investigations mapped out the phases of repair that occur separately in both the tendon and surrounding synovial sheath and have shown that the healing phases are more robust and prompt in the sheath than in the tendon body.[2]

Patients present with decreased active range of motion following surgical repair of flexor tendons. The average time from flexor repair to flexor tenolysis has been indicated to be around 8 months but includes a wide range from 2 to almost 25 months.[3]

Any surgery of the flexor tendon anatomy should only be undertaken if the patient is willing to commit to a rigorous course of physical therapy. The patient must have an intact alignment of skeletal structures, including bones, ligaments, and tendons, with no underlying arthrosis. The patient must have stable, mature scarring evident over all wound areas. The patient must have good strength in flexor and extensor muscles of the hand and must have intact nerves to flexor muscles. The patient must have good passive range of motion of affected tendons.Clinically, tenolysis is frequently offered if after a prolonged period of immobilization, passive flexion noticeably exceeds active flexion or if the patient exhibits a fixed contracture at a proximal interphalangeal joint.[3] The exact period prior to undergoing tenolysis is up for debate, and every patient is unique, but it is generally accepted that flexor tenolysis is recommended after the patient has concluded passive and active range-of-motion exercises for at least 3 months and has reached a plateau of progress.[2]

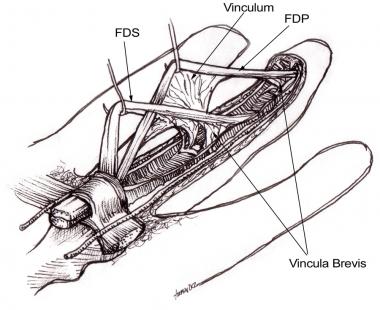

Two tendons contribute to active flexion, tendons from the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) muscles both attach to each finger. Both tendons are enclosed within an enclosed tendon sheath called a theca. The tendons connect the muscle bodies in the forearm with the fingers in the hand, passing through the carpal tunnel at the wrist. Tendons from the FDS insert on the base of the middle phalanx of each finger to flex the finger at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints. The FDP inserts into the base of the distal phalanx and flexes the finger at the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. Not all fingers are capable of independent movement in every individual because usually the tendons from the FDP are connected proximal to the individual fingers, and the only common exception to this is the tendon to the index finger.

There is in place an elaborate system of pulleys to prevent “bowstringing” or elevation of the tendon away from the palmar surface of the wrist during active flexion. The tough membrane that prevents this at the wrist is called the flexor retinaculum of the hand, and the tunnel for the tendons beneath is called the carpal tunnel. At the fingers, there are various annular or cruciate ligaments that perform a similar task by preventing the tendons from elevating. The precise number of annular or cruciate ligaments in each finger can potentially vary from individual to individual, but commonly there are 3-4 cruciate (C1-C4 proximal to distal) and 4-5 annular (A1-A5 proximal to distal) ligaments.

The first annular pulley, A1, lies at the head of the metacarpal bones, while the second through fifth annular ligaments, A2-A5, all attach to the bones on the finger. The cruciate ligaments generally are smaller than annular ligaments and are found between annular ligaments. Together, the cruciate and annular ligaments make a tunnel through which normally the flexor tendons pass.

Note the image below.

Flexor tendons with attached vincula. FDS, flexor digitorum superficialis; FDP, flexor digitorum profundus.

Flexor tendons with attached vincula. FDS, flexor digitorum superficialis; FDP, flexor digitorum profundus.

Tenolysis is absolutely contraindicated in patients with active infection, motor-tendon problems secondary to denervation, and unstable underlying fractures requiring fixation and immobilization. Relative contraindications include extensive adhesions, immature previous scars, and severe posttraumatic underlining arthrosis.

Workup

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved