Hallux valgus is considered to involve the following:

This condition can lead to painful motion of the joint and difficulty with footwear.

In the 19th century, the prevalent understanding of the bunion—hallux valgus—was that it was purely an enlargement of the soft tissue, first metatarsal head, or both, most commonly caused by ill-fitting footwear. Thus, treatment had varying results, with controversy over whether to remove the overlying bursa alone or in combination with an exostectomy of the medial head.

Because many surgeons considered these surgeries to be beneath them, a fuller understanding of the pathology of hallux valgus was slow to develop. Gradually, surgeons began to recognize that bunions could develop as a result of numerous different factors, that they tended to be familial, and that they often were associated with other foot deformities.

The first surgical treatment to address this deforming pathology was described by Reverdin on May 4, 1881, in a report delivered to the Medical Society of Genfer. In this procedure, a curved incision medial to the extensor hallucis longus was followed by incision of the periosteum, chiseling off of the exostosis, removal of a wedge of bone from behind the capitulum of the metatarsus, and suturing of the bone with catgut. This operation is the forerunner of all operations that aim to correct hallux valgus via osteotomy.

Since its inception, the Reverdin procedure has undergone many variations and modifications, including the addition of lateral releases and proximal osteotomies, in an effort to address deformity. Indeed, more than 100 procedures have been developed for the correction of hallux valgus. However, many were developed out of ignorance; some are even repetitions of previous procedures, with inconsistent rates of failure and success. Surgeons continue to reevaluate osteotomy for the treatment of hallux valgus to determine the most stable procedure with the fewest complications.

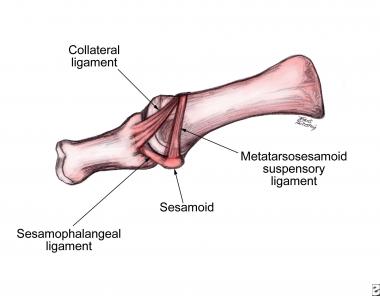

NextEffective treatment of hallux valgus depends on a solid understanding of the anatomy involved (see the images below).

Lateral view of first metatarsophalangeal joint with ligaments of sesamoid complex.

Lateral view of first metatarsophalangeal joint with ligaments of sesamoid complex.

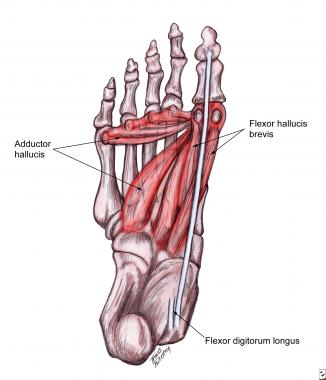

Plantar muscles that contribute to deforming forces.

Plantar muscles that contribute to deforming forces.

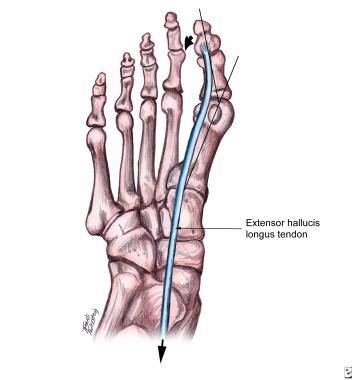

During the gait cycle, the hallux and digits generally remain parallel to the long axis of the foot, regardless of the degree of forefoot abduction (or pronation) occurring (see the image below). This is because of the pull of the conjoined adductor tendon, extensor hallucis longus, and flexor hallucis longus tendons. The tendons gain greater mechanical advantage the further the joint is displaced, with tension created in the medial aspect of the joint and compression laterally.

Line of pull of extensor hallucis longus causing metatarsal to deviate medially and hallux to deviate laterally.

Line of pull of extensor hallucis longus causing metatarsal to deviate medially and hallux to deviate laterally.

Medial tension causes the medial collateral ligaments to pull on the dorsomedial aspect of the first metatarsal head, causing bone proliferation. Lateral tension causes the sesamoid apparatus to fixate in a laterally dislocated position. Remodeling also occurs laterally in addition to medially, as evidenced by the increase of the proximal articular set angle or structural remodeling of the cartilage. Therefore, without correction of the biomechanical factors, excessive pronation continues, with propagation of the deformity.

Contrary to common belief, high-heeled shoes with a small toe box or tight-fitting shoes do not cause hallux valgus. However, such footwear does keep the hallux in an abducted position if hallux valgus is present, causing mechanical stretch and deviation of the medial soft tissue and aggravating symptoms. In addition, tight shoes can cause medial bump pain and nerve entrapment. Hallux valgus is known to have numerous etiologies, including biomechanical, traumatic, and metabolic factors.

The most common yet most difficult to understand etiology of hallux valgus is biomechanical instability. Contributing factors, if present, include gastrocnemius or gastrocnemius-soleus equinus, flexible or rigid pes planovalgus, rigid or flexible forefoot varus, dorsiflexed first ray, hypermobility, or short first metatarsal. Most often, excessive pronation at the midtarsal and subtalar joints compensates for these factors throughout the gait cycle.

Some pronation must occur in gait to absorb ground-reactive forces. However, excessive pronation produces too much midfoot mobility, which decreases stability and prevents resupination and creation of a rigid lever arm; these effects make propulsion difficult.

During normal propulsion, approximately 65° of dorsiflexion is necessary at the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, yet only 20-30° is available from hallux dorsiflexion. Therefore, the first metatarsal must plantarflex at the sesamoid complex to gain the additional 40° of motion needed. Failure to attain the full 65° because of jamming of the joint during pronation subjects the first MTP to intense forces from which hallux valgus can develop.

If the foot is sufficiently hypermobile as a result of excessive pronation, the metatarsal tends to drift medially and the hallux drifts laterally, producing hallux valgus. If no hypermobility is present, hallux rigidus develops instead.

Arthritic/metabolic conditions that may cause hallux valgus include inflammatory arthropathies such as gouty arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis (see the images below), and psoriatic arthritis, as well as connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Down syndrome, and generalized ligamentous laxity.

Rheumatoid arthritis. Note greater deformity of right foot (image left) versus left foot (image right).

Rheumatoid arthritis. Note greater deformity of right foot (image left) versus left foot (image right).

Rheumatoid arthritis. Note lateral deviation of hallux, cystic changes of metatarsal head, and hammertoe of lesser digits.

Rheumatoid arthritis. Note lateral deviation of hallux, cystic changes of metatarsal head, and hammertoe of lesser digits.

The myriad neuromuscular diseases that may cause hallux valgus include multiple sclerosis, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, and cerebral palsy.

Traumatic conditions that may cause hallux valgus include malunions with or without intra-articular damage, soft-tissue injuries of the hallux, and sequelae of dislocations.

Structural deformities that have been associated with hallux valgus include malalignment of articular surface or metatarsal shaft, abnormal metatarsal length, metatarsus primus elevatus, external tibial torsion, genu varum or valgum, and femoral retrotorsion.

Although hallux valgus is a common condition that accounts for a significant number of office visits to foot and ankle specialists, the incidence has not been documented accurately. Relatively few studies are available, and much of the information consists of empirical data with low levels of evidence.

According to the National Health Interview survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, this condition affects 1% of adults in the United States. Gould et al found that the incidence increased proportionately with age, from 3% in persons aged 15-30 years to 9% in persons aged 31-60 years to 16% in those older than 60 years.

Gould et al also reported a two- to fourfold higher incidence in females than in males. Whether this finding indicates a true sex-based dimorphism or whether it reflects differences in footwear remains to be determined.

The role of genetic predisposition has also been noted, with evidence to suggest familial tendencies.

No conclusive results have been reported to indicate racial or ethnic predisposition.

Hallux valgus is a complex deformity, and various approaches are available. To date, no satisfactory studies have been performed to compare the various procedures and their success rates. If the deformity and etiology are addressed successfully, the benefits of treatment far outweigh the risks.[1, 2]

Schuh et al studied changes of plantar pressure distribution during the stance phase of gait in patients who underwent hallux valgus surgery followed by multimodal rehabilitation. The study included 30 patients who underwent Austin and scarf osteotomy for correction of mild-to-moderate hallux valgus deformity and began a rehabilitation program 4 weeks postoperatively (once weekly for 4-6 weeks).[3] Plantar pressure analysis was performed preoperatively and at 4 weeks, 8 weeks, and 6 months postoperatively. ROM of the first MTP joint was also measured.[3]

The results of this study included an increased mean American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score, from 60.7 points preoperatively to 94.5 points 6 months after surgery, and the first MTP joint ROM increased at 6 months, with a significant increase in isolated dorsiflexion.[3] In the first metatarsal head region, maximum force increased from 117.8 N to 126.4 N, and the force-time integral increased from 37.9 N⋅s to 55.6 N⋅s. In the great toe region, maximum force increased from 66.1 N to 87.2 N, and the force-time integral increased from 18.7 N⋅s to 24.2 N⋅s.

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved