In 1883, Stimson first described the fracture patterns in lateral condyle fractures in his book Treatise on Fractures.[1] He described this type of fracture as beginning in the lateral metaphysis proximal to the condyle, coursing distally, and exiting through the articular surface through the medial trochlear notch or through the capitellotrochlear groove. In 1955, Milch recognized the significance of these fracture patterns as they related to elbow stability.[2] For this reason, the fracture patterns of the lateral condyle bear his name and are typically classified as either Milch I or Milch II fractures (see Presentation).[3, 4, 5]

The difficulties related to treatment of this fracture are both biologic and technical. Biologic problems are a result of the healing process and may occur with appropriate treatment and anatomic reduction. These problems include lateral spur formation with pseudo cubitus varus and true cubitus varus. Technical difficulties are the result of errors in management and may result in nonunion, malunion, valgus angulation, avascular necrosis (AVN), or a combination of these conditions.

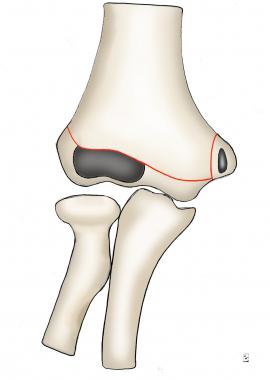

NextThe physis of the lateral condyle extends into the trochlear notch of the distal humerus (see the image below). Therefore, in some lateral humeral condyle fractures, the lateral crista of the trochlea may be part of the fracture fragment, leading to an unstable humeral ulnar articulation.

Diagram of intact distal humerus.

Diagram of intact distal humerus. The distal humerus is primarily cartilage at the age when these injuries typically occur, and knowledge of the secondary centers of ossification is necessary to understand the possible fracture patterns. Because of incomplete ossification, the fracture may appear subtle on radiographs as it courses through the cartilage anlage (see Workup).

The lateral condyle fracture is a Salter-Harris IV fracture pattern and follows physeal injury principles. (For more information about injuries of the growth plate, see Salter-Harris Fractures.) The fracture fragments in these patients are primarily cartilaginous as a result of the young age of the patients. The radiographic interpretation may be misleading because the visible fragment appears smaller than the actual size and, in addition, the amount of displacement is not appreciated.

In lateral condyle fractures, the displacement is greater than appreciated, and incongruity of the articular surface is present. Fractures with minimal displacement must be carefully monitored, as they have a high tendency to displace. Once these displaced fractures consolidate in a malunited position, treatment is difficult, dangerous, and fraught with complications. For these reasons, surgical reduction should be performed and is recommended within the first 48 hours after the fracture.[6]

Two theories of the mechanism of injury for this fracture exist. The first is the pull-off theory, in which avulsion of the lateral condyle occurs at the origin of the extensor/supinator musculature. This may occur as a varus stress is applied to the extended elbow with the forearm supinated. This is thought to be the most common mechanism of injury. The second is the push-off theory, in which a fall onto the extended hand leads to impaction of the radial head into the lateral condyle, causing the fracture.[7]

Lateral condyle fractures account for 17% of all distal humerus fractures and 54% of distal humeral physeal fractures. The frequency of lateral condyle fractures peaks in children aged 6 years. Most fractures occur in children aged 5-10 years. Cases have been reported in patients as young as 2 years and as old as 14 years.

In a study of 181 pediatric lateral condyle fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF; mean follow-up, 38 weeks; mean age, 5 years), Silva et al compared patients treated within the first 7 days after injury (group 1; n=133) and those treated 7-14 days after injury (group 2; n=48) in order to determine if there were any significant differences in outcome.[8] They reported no iatrogenic nerve injuries or vascular complications in either group, and mean operating time was similar. At the last follow-up appointment, the groups 1 and 2 were similar with respect to range of motion (ROM), complication rate (low in both), and percentage of satisfactory outcomes.

Silva et al also studied 191 pediatric lateral condyle fractures treated either with ORIF (group 1; n=163) or closed reduction with percutaneous pinning (CRPP; group 2; n=28) and followed for over 12 weeks.[9] They found CRPP to be a viable alternative for treating these fractures in cases involving limited initial displacement (2-4 mm); cosmetic results were better, operating times were shorter, and the complication rate was not significantly increased.

A study by Pennock et al yielded similar results for CRPP vs ORIF in pediatric lateral condyle fractures with 2.1-5.0 mm of displacement.[10]

Clinical Presentation

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved