Elbow collateral ligament insufficiency is commonly seen in sports participants involved in overarm-throwing sports such as cricket, baseball, and tennis. Trauma and postdislocation injuries are other common causes of collateral ligament injury, which can occur on either side of the joint. An understanding of the normal anatomy is required for diagnosis and successful surgical reconstruction.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

The elbow is one of the most congruous joints in the body. It consists of three articulations between the humerus, ulna, and radius within a capsule. The medial elbow collateral ligament resists valgus force and supports the ulnohumeral joint. The lateral ligament prevents rotational instability between the distal humerus and the proximal radius and ulna.

NextJobe et al first described double-strand reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) with use of a free tendon graft that was secured to the medial epicondyle and the proximal aspect of the ulna in a figure-eight fashion.[3]

Several complications are associated with this procedure, such as detachment of the flexor-pronator muscle group, extensive drilling of the medial epicondyle, and transposition of the ulnar nerve. Studies have focused on techniques of UCL reconstruction that minimize the potential for complications, particularly those related to the medial epicondyle and the ulnar nerve.[4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]

Medial elbow instability and posterolateral rotatory instability in overhead-throwing athletes are increasingly popular topics. The diagnosis and treatment have been the focus of much basic-science and clinical research. Methods for accurately diagnosing elbow instability continue to evolve. Patient history, physical examination, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as well as arthroscopic techniques for diagnosis and treatment, continue to play a vital role in differentiating between nonoperative and operative candidates.[6, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]

In a study of 72 professional baseball players who underwent arthroscopic or open elbow surgery, the most common causes of elbow symptoms were posteromedial olecranon osteophyte (65%), UCL injury (25%), and ulnar neuritis (15%). In the United States, the estimated incidence of all baseball-related overuse injuries is 2-8% per year (20-50% of these injuries occur in adolescents and school-age children).

The true worldwide incidence of sports-related injuries is not known, because a large number of athletes never seek medical care and because the statistical data are not available from various countries.[1]

The two most common causes of elbow instability are sports (commonly chronic) and trauma (acute onset, as with ligamentous injuries in elbow dislocation).

During the throwing motion, high loads of valgus stress on the elbow joint results in tension on the medial structures (ie, medial epicondyle, medial epicondylar apophysis, and medial collateral ligament [MCL] complex) and compression of the lateral structures (ie, radial head and capitellum). Repeated MCL stress due to medial tension overload may result in MCL strain or rupture. This chronic injury may lead to development of ulnar traction spurs, deposition of calcium, and medial ligament instability.

Injuries associated with specific sports include the following:

UCL injuries can manifest as acute ligament tears following a single valgus stress or as overuse sprains following repetitive valgus overloads. Repetitive medial stress can also cause attenuation and microstretching of the UCL complex, causing instability over time.

Maximal MCL stress occurs when the elbow remains flexed between 60 º and 75 º and the wrist begins to cock in preparation for the throw in the late cocking phase of throwing, as well as in the acceleration phase, when maximal humeral external rotation occurs.

The common pathway of posterolateral instability includes the following:

Recurrent microtrauma of the skeletally immature elbow joint in children can lead to little leaguer's elbow, a syndrome that encompasses the following:

With posterior dislocation of the elbow joint, dislocation begins on the lateral side of the elbow and progresses to the medial side in three stages, as follows:

Patients with posterolateral rotatory instability often remember a distinct traumatic event, most often a posterior dislocation. The athlete has a sense of instability and reports a snapping sensation, which causes pain when throwing.

Patients with olecranon impingement syndrome often complain of posterior elbow pain with locking or snapping when throwing. The pain is worst when the elbow is extended. Throwers often complain of loss of velocity and control.

Patients with an anterior capsule strain present with anterior elbow pain, which often is aggravated by repetitive hyperextension and is not affected by elbow flexion.

Patients with an MCL sprain experience referred pain down the arm into the little finger and ring finger, which mimics the symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome (a more common reason for this condition is ligament laxity in the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae or in the UCL, not a pinched nerve).

MCL insufficiency manifests as medial elbow pain with laxity to valgus stress.

Medial epicondylar apophysitis is caused by repetitive valgus stress and generally manifests as progressive medial pain, decreased throwing effectiveness, and decreased throwing distance.

Medial epicondyle fracture manifests as point tenderness and swelling over the medial epicondyle, often with an elbow flexion contracture greater than 15°.

Neurologic injuries such as C8-T1 radiculopathy and ulnar neuritis, though uncommon in children, can manifest as medial elbow pain and should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Surgical reconstruction is indicated in the following patients:

There are three primary static constraints on elbow instability, as follows:

There are four secondary restraints on elbow instability, as follows:

Both the MCL and the LCL are strong fan-shaped thickenings of the fibrous joint capsule. These ligaments prevent excessive abduction and adduction of the elbow joint. The AL wraps around the radial head and holds it tight against the ulna.

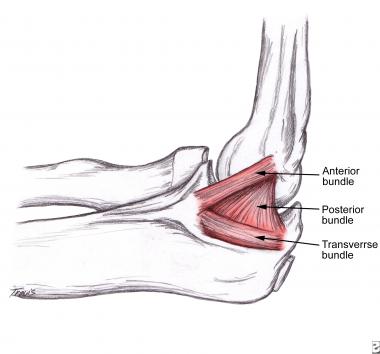

The humeral origin of the MCL lies posterior to the axis of elbow flexion, creating a cam effect; hence, anterior fibers are stressed in extension, and posterior fibers are stressed in flexion. The MCL has the following three major portions (see the image below):

Schematic diagram of medial collateral ligament of elbow shows 3 bundles. Anterior bundle is major stabilizer of elbow to valgus stress.

Schematic diagram of medial collateral ligament of elbow shows 3 bundles. Anterior bundle is major stabilizer of elbow to valgus stress.

The anterior oblique ligament is the primary stabilizer of the elbow for functional range of motion (ROM) from 20 º to 120º. It arises from the anteroinferior surface of the medial epicondyle and inserts at the sublimis tubercle, adjacent to the joint surface. Given that a significant portion of the anterior band inserts near the coronoid process, MCL instability may result from low coronoid process fracture.

The anterior oblique bundle has two subportions, anterior and posterior. The anterior band is the primary restraint to valgus rotation at 30 º, 60 º, and 90º of flexion and is a coprimary restraint at 120º; it is more likely to be injured with the elbow in extension. The posterior band is the coprimary restraint at 120º; it is more likely to be injured in flexion (though injury to this band usually occurs along with injury to the anterior band).

The posterior oblique ligament is a weak, fan-shaped thickening of the joint capsule, which arises at the posterior aspect of the medial epicondyle and inserts over the olecranon; it forms the floor of the cubital tunnel and functions as a secondary stabilizer only at 30º of flexion.

The transverse ligament is a constant anatomic structure that is intra-articularly visible within the lower part of the medial joint capsule; it strengthens the articular joint capsule and contributes to elbow stability.

The MCL is the primary medial stabilizer of the flexed elbow joint. In full extension, it provides about 30% of stability, versus about 54-70% in 90º flexion. The radial head is an important secondary stabilizer in extension, as well as in flexion. After excision of the radial head alone, there is a 30-33% loss in valgus stability of the elbow, which does not significantly improve even after replacement with a silicone rubber radial head.

Resection of the anterior band of the MCL will result in gross instability, except in full elbow extension. Resection of both the MCL and the radial head results in gross instability of the elbow and may produce subluxation or dislocation of the elbow. The anterior bundle of the MCL is tested with the elbow in 90º of flexion.

Anatomically, the LCL consists of a ligamentous expansion proceeding down from the lateral epicondyle to the ulna (a major expansion, which inserts into supinator crest of the ulna) and also sends expansions down to the AL and the radius.

The LCL has a greater role with increased flexion of the elbow. LUCL deficiency leads to posterolateral rotatory instability. Additional deficiency of the RCL results in dislocation of the elbow.

The ECU (extensor carpi ulnaris) tendon and the supinator tendon merge with the LCL and resist posterolateral instability.

Relative contraindications for surgical treatment include the following:

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved