Lipofibromatous hamartoma (LFH) is a rare, benign fibrofatty tumor composed of a proliferation of mature adipocytes within peripheral nerves, which form a palpable neurogenic mass. It affects the median nerve in 66-80% of cases, causing pain and sensory and motor deficits in the affected nerve distribution; this predilection remains unexplained.[1] Although LFH was first described in the English literature in 1953, fewer than 90 cases have been documented.[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

Starting in the late 1950s and continuing into the next decade, numerous authors reported cases of extraneural fibromas causing compression neuropathy of peripheral nerves; however, these cases were yet to be described in relation to one another.[1, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] In 1969, Johnson and Bonfiglio coined the term lipofibromatous hamartoma, accurately describing the entity and its relation to carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS).[6]

In addition to the unexplained predilection of LFH for the median nerve, cases of fatty infiltration of the brachial plexus, ulnar, radial, peroneal, plantar, and digital nerves have also been reported.[6, 1, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19] To date, several terms besides LFH have been used to describe this condition including fibrolipomatous hamartoma, intraneural hamartoma, neural fibrolipomatosis, and neural fibrolipoma.

The differential diagnosis includes ganglion cysts, vascular malformations, traumatic neuromas, schwannomas, neurofibromas, and lipomas. In 1994, Guthikonda et al divided lipomatous masses into 4 types according to their location within the parent nerve[20] :

Because of the infrequency of the diagnosis, researchers have been unable to perform any randomized-controlled studies examining the treatment of LFH. Consequently, no standard of care has been established for this condition. Some surgeons recommend neurolysis, whereas others advocate tunnel decompression. As more cases of LFH are reported in the literature, further insight will be gained into appropriate management.[21]

NextThe pathophysiology of lipofibromatous hamartoma (LFH) is unknown. The tumor is known to have an unexplained predilection for the median nerve (66-80% of cases), causing pain and sensory and motor deficits in the affected nerve distribution.[1] LFH also affects the brachial plexus, ulnar, radial, peroneal, plantar, and digital nerves.[16, 17, 18]

A fundamental knowledge of the anatomic courses of the relevant nerves helps distinguish LFH from other hand tumors. LFH typically presents with a soft mass in the body of the nerve, whereas other neoplasms may occur in other sites.

A congenital origin of LFH, with or without macrodactyly, has been suggested, but the etiology of this condition remains unclear. LFH in the posttraumatic setting, also showing the characteristic fatty infiltrate on biopsy, has been reported.

Most cases of lipofibromatous hamartoma (LFH) occur within the first 3 decades of life, with a mean age of 22.3 years in isolated cases and 22 years in cases with macrodactyly. Silverman and Enzinger reported 26 cases of upper- and lower-extremity LFH: 7 with macrodactyly and 19 without.[18]

The term macrodystrophia lipofibromatosa refers to LFH that occurs in the presence of frank macrodactyly.[22] A 2:1 female-to-male ratio has been reported for cases with macrodactyly, and a 1:1 ratio has been found for cases without macrodactyly.[18, 19]

Complicating the scenario even further is the considerable overlap with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome, congenital lymphedema, hypertrophic mononeuritis, and hereditary hypertrophic interstitial neuritis of Dejerine-Sottas.[6]

Patients with lipofibromatous hamartoma (LFH) typically present with gradually enlarging nontender lesions (see the image below). They may have neurologic symptoms in the distribution of the affected nerve. Unilateral elsions on the thenar areas or fingers may be present.[23] Because LFH often involves the median nerve, the presentation of median nerve LFH shares considerable overlap with carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS).[24, 25] Affected individuals complain of numbness and tingling along the volar aspect of the hand and fingers. Motor deficits are a late finding.

LFH shares considerable gross overlap with neurofibromatosis, at time necessitating both radiologic and microscopic investigation for accurate differentiation. Differentiation of the 2 conditions is important: LFH is a benign tumor, whereas neurofibromatosis can progress to frank malignancy, and thus, the 2 entities are treated quite differently. Neurofibromatosis and LFH are further confounded because the former rarely occurs with macrodactyly, whereas the latter can be present with or without macrodactyly.[26]

Grossly, LFH tumors are irregular, yellow masses (see the image below). Barsky reported isolated cases of macrodactyly with fatty infiltration of the digital nerve and marked overgrowth of all tissue types.[26] Johnson and Bonfiglio were the first to propose a microscopic relation between macrodactyly, neurofibromatosis, and LFH, suggesting that macrodactyly involves proliferation of all involved tissues, including skin and bone, and fatty enlargement between nerve fasciculi in the absence of thickening of the epineurium, perineurium, and endoneurium.

Intraoperative photograph shows lipofibromatous hamartoma and typical gross appearance. Multiple soft, gray-yellow lobulated masses (arrows) are present within epineural sheath of radial digital nerve of right index finger. Epineurium of digital nerve displays extensive perineural fibrosis. Image reprinted with permission from American Journal of Roentgenology.

Intraoperative photograph shows lipofibromatous hamartoma and typical gross appearance. Multiple soft, gray-yellow lobulated masses (arrows) are present within epineural sheath of radial digital nerve of right index finger. Epineurium of digital nerve displays extensive perineural fibrosis. Image reprinted with permission from American Journal of Roentgenology.

Neurofibromatosis includes a disorganized proliferation of the epineurium, perineurium, and endoneurium in the absence of fatty infiltration. Finally, LFH involves disorganized overgrowth of epineurium, perineurium, and endoneurium with fatty infiltration, no involvement of surrounding tissues, and no inflammation.[6]

The appearance of lipofibromatous hamartoma (LFH) on diagnostic imaging (ie, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) is now thought to be pathognomonic for the soft-tissue neoplasm.

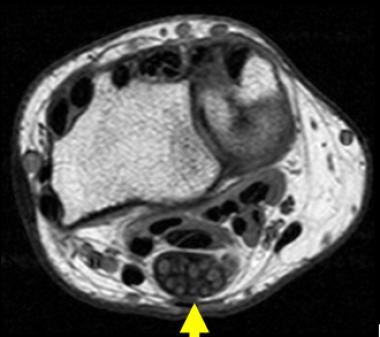

The characteristic appearance of LFH on MRI is that of serpiginous, low-intensity structures surrounded by fat, demonstrating high intensity on T1-weighted images and low intensity on T2-weighted images. On the axial cuts, the nerve fibers are often described as having a coaxial-cable appearance (see the first image below), whereas on coronal sectioning, they are described as resembling spaghetti (see second image below).[18]

Axial T1-weighted image of 40-year-old woman who experienced several years of paresthesias in her median nerve distribution and mass in her wrist. Note pathognomonic coaxial-cable appearance of involved nerve.

Axial T1-weighted image of 40-year-old woman who experienced several years of paresthesias in her median nerve distribution and mass in her wrist. Note pathognomonic coaxial-cable appearance of involved nerve.

Coronal T1-weighted image of 40-year-old woman who experienced several years of paresthesias in her median nerve distribution. On coronal sectioning, lipofibromatous hamartoma is described as resembling spaghetti.

Coronal T1-weighted image of 40-year-old woman who experienced several years of paresthesias in her median nerve distribution. On coronal sectioning, lipofibromatous hamartoma is described as resembling spaghetti.

LFH demonstrates low signal on spin-echo T1-weighted and fast-spin-echo T2-weighted images.[27] Spin magnetic resolution of LFH shows a characteristic pattern of longitudinally oriented fibers with interspersed signal voids that represent nerve fascicles being infiltrated by fat.[18]

Although 1 case of atypical MRI findings was reported with LFH in the distribution of the medial plantar nerve, differentiation of LFH from other lesions on the basis of MRI has now become relatively straightforward.

Whereas LFH displays uniform fatty infiltration, intraneural lipomas show focal fatty masses separated from the individual nerve bundles.[27] LFH differs from ganglion cysts, traumatic neuromas, macrodactyly, Dejerine-Sottas syndrome, and plexiform neurofibromas in that these show high-intensity signals on T2-weighted imaging.[28] Although both hemangiomas and LFH demonstrate high-intensity signals on T1-weighted imaging, only hemangiomas have a markedly increased uptake on T2-weighted imaging as well.[28]

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) can aid in the diagnosis of lipofibromatous hamartoma (LFH). LFH typically stains positive for CD34, S-100 protein and vimentin. IHC yields negative results for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), desmin, and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).[16]

Ultrasonographic studies are now being used to provide further support for the diagnosis of LFH, but they cannot be used alone to establish the diagnosis.[29]

Before the substantial advances in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the diagnosis of lipofibromatous hamartoma (LFH) was strongly supported by imaging modalities and confirmed by tissue biopsy. Currently, however, the diagnosis is now made solely on the basis of MRI.[30]

Sectioning of the involved nerve typically demonstrates nerve bundles that are entrapped within a fibrofatty, fusiform mass.[6] LFH involves disorganized overgrowth epineurium, perineurium and endoneurium with fatty infiltration, no involvement of surrounding tissues and no inflammation.[6] Histologic findings are limited to perineural and endoneural fibrosis with axons that are normal in size or atrophic and with fatty infiltration around the nerve branches.[28]

No current guidelines for the treatment of lipofibromatous hamartoma (LFH) are available. The surgeon and the patient must weigh the potential risks and benefits of surgery against those of conservative management. Overall, treatment is based on the symptoms of the condition, considered on a case-by-case basis. Although some patients with LFH experience no neurologic or functional complications, others do. Medical management has no role, and surgery is reserved for those with neurologic deficits.

Because of the tumor’s intimate involvement with the nerve, LFH is often accompanied by a degree of neurologic morbidity. If the risk of nerve damage is low and nerve involvement is minimal, surgical debulking for cosmetic reasons can be undertaken. However, in the face of advanced nerve involvement, indications for intervention are progressive and unrelenting neurologic deficits.

Several problems may complicate the case-by-case surgical approach to the treatment of LFH. One such problem involves the treatment of the symptoms of nerve compression, typically carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). Although it is generally held that carpal tunnel decompression should be undertaken for relief of paresthesias, some authors strongly advocate waiting for the tumor to become symptomatic before surgery, mostly in younger children.[5, 31, 32, 33]

Another problem involves the management of cases associated with macrodactyly. The following options are available:

With regard to debulking, a review of 8 cases found that 3 patients reported a decrease in mass size from 1-year to 3-year follow-up, 4 noted no change from 2-7 years out, and 1 reported an increase in tumor mass after surgery.[6]

In many cases, both neurolysis and excision of the main trunk of the median nerve can lead to abnormal 2-point tactile discrimination and a loss of sensory distribution after operation in adult patients.[29] Furthermore, microdissection of the median nerve has led to ischemic complications in 1 reported case and has been unsuccessful in others.[28, 29, 34] One case of successful median nerve excision in the presence of a Martin-Gruber anastomosis has been reported.[35, 36]

Amadio et al reported on significant debulking of tissue followed by distal digital nerve excision.[5] Because of the considerable cutaneous overlap in the hand, the authors suggested debulking followed by rotation of the excess skin from the dorsal aspect to the volar aspect of the affected digits to restore sensation.[5] Although this does not fully restore the dermatomal distribution of sensation, it does offer a degree of sensation that would have been lost either with no treatment or with nerve excision alone.

Preoperative management, surgical planning, and postoperative management are all similar to those of CTS surgery. As with CTS surgery, follow-up can be performed on an outpatient basis. Patients can be seen at 1 week, by which time their pain should have subsided considerably. Restoration of nerve function and resolution of paresthesias vary from case to case.

Reports on the efficacy of nerve excision tumor debulking and microsurgical intraneural dissection have been mixed.[37] Two studies described a complete loss of neurologic function after complete excision, whereas nerve excision and grafting have yielded favorable results in children younger than 5 years.[5, 31, 32] Children may have a capacity for reeducation of nerve sensibility that adults lack.[5, 31, 32]

The outcomes and prognosis of surgical therapy for lipofibromatous hamartoma (LFH) have ranged from loss of sensory and motor function to full return of both motor and sensory function. Numerous factors affect prognosis, including the degree of involvement, the size of tumor burden, the age of the patient, and surgical technique.[5] Because no randomized controlled studies have examined the treatment of LFH, controversy still arises regarding the most suitable approach to the problem.

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved