Arthrocentesis (joint aspiration) is a basic diagnostic tool in the evaluation and treatment of acute joint pathology. It may be performed not also for diagnosis but also for therapy. Synovial fluid analysis allows distinction between inflammatory and noninflammatory conditions and provides direct proof of crystal arthropathy, infection, and hemarthrosis. Synovial aspiration and corticosteroid injections and infiltrations carry minimal risk to the patient when properly indicated and performed.

The wrist joint is anatomically complex (see Wrist Joint Anatomy), but most of the intercarpal spaces communicate with the radiocarpal joint, which may be entered from a dorsal approach. This is, therefore, the preferred site of aspiration of the wrist joint.

NextDiagnostic indications for wrist arthrocentesis include the following:

Aspiration and analysis of synovial fluid are helpful for diagnosis when septic arthritis, crystal synovitis, or bleeding is the suspected cause of a joint, bursal, or tendon sheath condition. In addition, in patients who have poorly defined forms of arthritis, knowledge of the nature of the synovial fluid, particularly the inflammatory cell content, complements findings from the history and physical examination and helps provide the basic framework for diagnosis and treatment (see Table 1 below).

Table 1. Assessment Parameters for Synovial Fluid (Open Table in a new window)

Parameter Normal Osteoarthritis Rheumatoid and Other Inflammatory Arthritis Septic Arthritis Gross appearance Clear Clear Opaque Opaque Volume, mL 0-1 1-10 5-50 5-50 Viscosity High High Low Low Total white blood cell count, cells/μ L < 200 200-10,000 500-75,000 >50,000 Polymorphonuclear cells, % < 25 < 50 >50 >75

Wrist arthrocentesis can be performed for diagnosis of acute arthritis. Most cases of acute wrist arthritis are due to calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate pseudogout, gout, and septic arthritis.

Therapeutic indications include the following:

In patients with tense joint effusions, aspiration of synovial fluid provides prompt relief of pain and permits the patient to move or bear weight on the affected joint. In hemarthrosis or septic arthritis, the blood or pus within a synovial cavity may be damaging to the joint cartilage and synovial membrane. Evacuation of the inflammatory fluid may help ameliorate joint damage. Large articular effusions should be drained as fully as possible to decrease pressure, improve synovial circulation, and prevent muscle atrophy.

Other indications can be for injection in rheumatoid arthritis (RA),[1] other sterile synovitises, and osteoarthritis (OA). OA can be secondary to calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD) or hemochromatosis.

Few absolute contraindications to joint or soft tissue aspirations and injections exist.

If infection of the joint is suspected, fluid should almost always be aspirated from a joint. For other indications, the procedures should probably be avoided if infection is present in the overlying skin or subcutaneous tissues or if bacteremia is suspected.

The presence of a significant bleeding disorder or diathesis or the presence of severe thrombocytopenia may also preclude joint aspiration. If the procedure is deemed necessary for diagnosis or therapy, it may be carried out with appropriate precautions to address the bleeding disorder (eg, after an injection of factor VIII in a patient with hemophilia). Warfarin anticoagulation with international normalized ratio (INR) values in the therapeutic range is not a contraindication to joint or soft tissue aspiration or injection.

Arthrocentesis through an area of irregular or disrupted skin (eg, psoriasis) should be avoided because of the increased numbers of colonizing bacteria in such areas.

Aspiration of a joint with a prosthesis in it carries a particularly high risk of infection and is often best left to surgeons using full aseptic techniques.

If infection is the suspected underlying cause of the musculoskeletal problem, corticosteroids should not be injected; if they are, the infection may be exacerbated.

For local anesthesia (see Local Anesthetic Agents, Infiltrative Administration), the skin and subcutaneous tissues may be infiltrated down to the level of the periarticular lesion or joint capsule with 1% or 2% lidocaine via a small needle (25 or 27 gauge). However, many experienced clinicians prefer to use topical ethyl chloride or no anesthetic at all. This is often appropriate for joint aspiration because anesthetizing the capsule is difficult. A single quick needle thrust may be much less painful than the administration of local anesthesia.

Aspiration of the wrist does not require specialized equipment.

Sterile technique must be followed during the procedure. Many experienced operators do not use sterile gloves. In this case, a no-touch technique is employed, in which palpation and marking of the puncture site precedes application of the antiseptic. The area is not touched after the initial marking. Nonsterile gloves should still be worn to protect the operator.

A 20-gauge needle should be used. Occasionally, for septic arthritis, an 18-gauge needle may be required, if the fluid is too viscous to allow aspiration through a smaller needle.

A 5-mL syringe is usually the most appropriate size. A "reciprocating syringe" has been developed to improve procedural performance. Some randomized data suggest benefits when compared to conventional syringes for joint aspiration.[2]

Forceps may be useful for holding the needle when changing the syringe between aspiration of the joint and injection of medication into the synovial cavity.

The patient should be placed in a comfortable supine or recumbent position. This enhances relaxation and guards against possible fainting. The wrist should be slightly palmar flexed to facilitate the performance of the procedure.

The skin must be carefully cleaned with an antiseptic agent. Before this is done, bone and other landmarks must be identified by means of palpation, and the needle site must be marked (eg, with a thumbnail imprint in the skin or a skin marker).

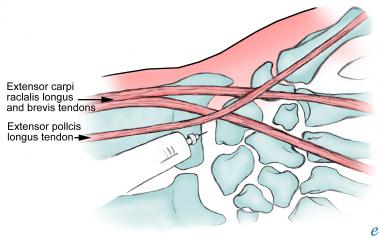

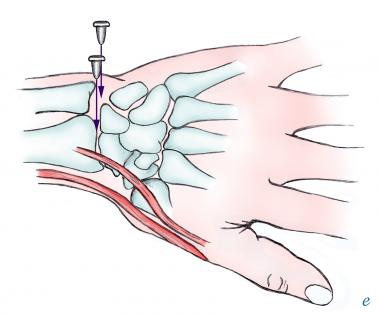

Insert the needle dorsally just distal to the radius and just ulnar to the anatomic snuff box. Avoid the associated tendons (extensor carpi radialis brevis and extensor pollicis longus). Direct the needle perpendicular to the skin. If bone is hit, pull the needle back and redirect it slightly toward the thumb.

With the proper technique, the needle passes freely through the extra-articular tissues and a "pop" is felt as the needle enters the joint. The ease with which the fluid can be withdrawn depends on needle size, viscosity of the fluid, degree of effusion, and presence of any fibrin clots. (See the images below.)

Injection of wrist joint.

Injection of wrist joint.

Arthrocentesis of wrist: medial and lateral approaches.

Arthrocentesis of wrist: medial and lateral approaches.

Free flow of fluid is often suddenly interrupted when the needle end is clogged by synovial membrane or debris. Rotating the needle, withdrawing it slightly, or even reinjecting a little of the fluid often helps to unclog the needle and allow additional fluid to be withdrawn.

A 22- to 25-gauge needle, 1.25-2.5 cm long, is usually adequate. In some cases, a 20-gauge or even an 18-gauge needle may be advisable (see Equipment). Occasionally, up to 3-5 mL of fluid may be obtained from the wrist by aspiration, and, if indicated, 0.5 mL of steroid may be injected into the space.

At the end of any injection procedure, the needle should be swiftly withdrawn, and light pressure should be put on the needle site in the skin.

Bedside ultrasonography may be useful as an adjunct for joint aspiration by helping to localize the optimal site for needle placement.[3] Ultrasonography may also help differentiate joint effusion from periarticular disease.

Surprisingly few complications arise as results of arthrocentesis and corticosteroid injections into the wrist joint.

The most significant issue is the risk of infection. Care must always be taken to use sterile technique. Corticosteroids are contraindicated in patients with septic arthritis. The estimated risk of septic arthritis following aspiration or corticosteroid injection is estimated to be between 1 in 2,000 and 1 in 15,000 procedures.

Other complications can arise from misplaced injections. The best described complication is tendon rupture following corticosteroid injections for tendonitis. The risk of this complication can be minimized by avoiding injection into the tendon itself. No therapeutic agent should be injected against any unexpected resistance. Occasionally, nerve damage can also result from a misplaced injection (eg, median nerve atrophy following attempted injections for carpal tunnel syndrome).

Other indications exist for performing aspiration or injections about the wrist.

Inflammation and swelling of the extensor tendon sheaths over the dorsal wrist may be due to a number of inflammatory processes (most commonly, rheumatoid arthritis [RA], but occasionally crystal-induced arthritis or infectious processes).

The areas of swelling are often well defined and close to the surface, and they are easily entered with direct aspiration, usually at a 30º-45º angle, with the needle directed along the course of the swollen tendon.

Fluid is often easily obtained. In some patients (those with rheumatoid arthritis, in particular), proliferative synovial tissue limits the amount of fluid that can be aspirated.

After aspiration, the area can be injected with 0.5 mL of corticosteroid mixed with 0.5-1 mL of lidocaine, if indicated.

De Quervain tenosynovitis, a common overuse syndrome involving the tendons at the radial aspect of the anatomic snuff box, is often helped by local injection of the tendon sheath.

After examination, the area of most tenderness along the course of the tendon should be marked and the needle should be inserted either proximally or distally, directed almost parallel to the skin. As the needle is advanced, 0.5 mL of steroid with 0.5-2 mL of lidocaine can be injected along the tendon sheath, and a palpable bulge is usually felt along the tendon.

Inflammation with swelling in the many flexor tendons in the carpal tunnel area may result in median nerve compression (see Carpal Tunnel Syndrome). Injection in this area has the potential to relieve symptoms by reducing this inflammation. This area should be defined by making a mark on the volar aspect of the wrist along the flexor tendons, on the ulnar side of the long palmar tendon, approximately 2.5 cm proximal to the distal wrist crease.

A 22- to 25-gauge needle may be introduced perpendicular to the skin or at an angle of 30º-45º, directed proximally or distally along the course of the tendon. The needle should be introduced about 1.25-2.5 cm, and the area should be injected with 0.5 mL of steroid with 0.5-1 mL of lidocaine. If the needle meets obstruction, or if the patient experiences paresthesias, the needle should be withdrawn and redirected to avoid injecting into the body of a tendon or into the median nerve itself.

Small, often hard, nodular structures known as ganglia are frequently present around the hands and wrists, and they may occur in many other areas near joints or tendons. These structures usually contain a thick gelatinous substance that is difficult to aspirate. Although surgical excision may be generally preferable for treatment of wrist ganglia, wrist arthrocentesis and intra-articular steroid injection may be worthwhile options for some patients.[4, 5]

In cases in which pain, tendon dysfunction, or nerve entrapment symptoms are bothersome to the patient, aspiration may be attempted, usually with an 18- to 20-gauge needle. Even if no fluid is obtained, the process of puncture occasionally causes the structure to dissipate its contents, and symptoms are relieved. A small amount (0.2-0.5 mL) of steroid with lidocaine may be injected in an attempt to prevent reaccumulation of fluid.

Copyright © www.orthopaedics.win Bone Health All Rights Reserved